Syntax differences hide splits in meaning

Fri 7 Sep 2018 by mskala Tags used: linguistics, philosophyOne way people divide themselves into tribes is over word usage. If one tribe claims a certain sequence of letters has a certain meaning, and another claims it has a different meaning, then there are plenty of opportunities for them to misunderstand each other or each declare the other Wrong. There may not be a lot we can do about it when there's a direct disagreement on the one true meaning of exactly one word.

However, human language is more complicated than that. One sequence of letters may not have just one meaning and in particular, it may be used in more than one syntactic role such that the different ways of using it have different meanings. At that point it may not even be right to call it one "word"; it is two words, with different meanings and also different grammar, that only happen to share a spelling. And if two tribes use words that differ in this way, maybe there is some hope of building a bridge between them by making clear that their uses of the same sequence of letters really refer to different things and do not need to have identical meaning. That is what I'd like to talk about here: how different syntax can be a clue to different meaning.

On notation

Throughout this piece I will use an asterisk "*" to mark negative examples that do not reflect standard prescriptively correct language use, and the following subscripts which will be described in detail later.

- NC - "noun, countable"

- NM - "noun, mass"

- VI - "verb, intransitive"

- VT - "verb, transitive"

- VD - "verb, ditransitive"

- A - "adjective"

Mass and countable nouns

In English grammar, words called nouns refer to entities that might for instance be the subjects or objects of verbs. There are nouns that refer uniquely to specific individuals - basically names and words that function like names - and these are called proper nouns; but proper nouns do not enter much into the ideas I'm discussing here. Right here I'm more interested in the kind of nouns where a single word might refer to any instance of a class, with specific identity possibly expressed in other ways than built into the noun. For example, "apple," "water," "data," and "privilege."

Some nouns are called countable nouns (other terms for this also exist). Countable nouns are the kind people most usually think of first when they talk about nouns in English, and countable nouns have a number of important syntactic and semantic properties.

- They represent things that naturally exist in the form of individuals, of which an integer number (like one, two, or three) may exist.

- They have separate "singular" and "plural" forms, the plural most typically distinguished by adding "-s" to the singular although some other suffixes exist used for certain nouns, a few countable nouns change in other ways between singular and plural (such as foot/feet), and a very few countable nouns have surface-identical singular and plural forms (such as sheep/sheep).

- When using a countable noun it is syntactically required to select either the singular or plural form and thereby indicate whether one is talking about one or more than one of the things indicated by the noun.

- If it is desired to include both the possibilities of one and more than one, then it is necessary to explicitly indicate it by saying something like "one or more," but "two or more" is implicit in the use of the plural if there is no further specification.

- When using the singular form, it is usually also syntactically necessary to attach an article ("a," "an," or "the"), which basically indicates whether the listener is expected to know the identity of the specific individual mentioned.

- When using the plural form, "the" is allowed but "a" and "an" are not, and it is also allowed to use the plural noun without an article. The choice between "the" or no article with a plural indicates a difference in generality level similar to the difference between using "the" and using "a" or "an" with a singular.

- A plural form can be used with a number to indicate how many items are described, if more than one. If the number is exactly one, it may be attached to a singular form to emphasize the number, although "one" is implicit with the singular form anyway. A singular noun can also be used in certain phrases to indicate nonzero quantity less than one (e.g. "half an apple"), although such non-integer quantities do not always combine well with countable nouns in general. No extra words are needed to attach an integer to the countable noun.

- The quantity question about a countable noun is "how many?"

Here are some examples of sentences using countable nouns, indicated by the subscript NC for "noun, countable":

(1) Alice read a bookNC.

(2) Bob threw twelve pitchesNC.

(3) Carol rode her horseNC to a nearby townNC.

(4) Dave ate an appleNC.

(5) The armyNC invaded Poland.

Note the absence of "a" or "an" on horseNC in sentence (3); the use of the word "her" to identify which horse is meant makes an article unnecessary (and indeed, forbidden) in this sentence despite that "horse" is a singular countable noun. All the names Alice, Bob, Carol, Dave, and Poland are proper nouns.

But there are other nouns in English besides proper and countable nouns: there are also mass nouns. Mass nouns typically describe substances like liquids that exist in continuously variable quantities rather than as naturally indivisible items, or else abstractions that somehow are thought of like substances. Mass nouns have different syntax and semantics from countable nouns.

- Mass nouns represent things that naturally occur in continuously variable quantities, or as abstractions for which quantity is not a particularly meaningful concept. Using a mass noun by itself does not say anything about its quantity.

- Mass nouns do not have separate singular and plural forms.

- Mass nouns are not used with the articles "a" and "an"; they are used with "the" or no article in much the same pattern as the plural forms of countable nouns.

- This is not syntactically required, but it is possible to specify the quantity of something indicated by a mass noun. To do so it is normally necessary to specify a unit of measure, which is a special countable noun that can be attached to the mass noun with the preposition "of." The unit of measure takes a plural or singular form and an article or number, like other countable nouns.

- Different units make sense for different mass nouns, but more than one unit may be allowed for the same mass noun and they may have different meanings, as "two slices of bread" or "two loaves of bread."

- The quantity question about a mass noun is "how much?"

Here are some examples of sentences using mass nouns, marked with the subscript NM for "noun, mass."

(6) Alice picked a baleNC of cottonNM.

(7) Bob measured out fifty milligramsNC of phenolNM.

(8) Carol is allergic to phenolNM.

(9) Dave fell in the waterNM.

(10) WaterNM is an important elementNC of natureNM.

In (6) and (7), the units of measure baleNC and milligramsNC, which are countable nouns, are used to specify the quantities of the mass nouns cottonNM and phenolNM. In (8), there is no quantity specified; this sentence refers to all the phenolNM in the world that does or could exist, all of it being equally dangerous to Carol. Similarly, waterNM and natureNM in (10) refer to general, abstract concepts. But in (9), the word "the" means that the waterNM is more specific: some definite body of water in particular, even if which one is not explained in this sentence.

Most nouns have a strong preference for being countable or mass, but it is fairly common for a noun that is normally mass to be used in a countable way. Doing so often changes the meaning.

(11) Waiter! We'll have one bourbonNC, one scotchNC, one beerNC, and three watersNC, please.

(12) There are five cheesesNC on the pizzaNC.

(13) The lemmingNC with the locketNC hid inside a big round cheeseNC.

(14) Dave fell in the polluted watersNC of the Love Canal Superfund Site.

In (11), the normally mass nouns for various drinkable liquids are being used as countable nouns to refer implicitly to standard servings of the liquids in question. This is a fairly specialized technical context: it's acceptable specifically in the implied situation of ordering in a restaurant, but would not be treated as standard or correct in most other pragmatic contexts. In other contexts a similar usage might instead be understood to refer to counting different types of bourbon, scotch, beer, and water, as in the next example sentence.

In (12), the normally mass noun cheeseNM is changed to a countable noun cheeseNC to refer to countable types of cheeseNM. That is a common pattern: normally-mass nouns used in a countable way often represent categories or types of the original mass noun. But that is not always what changing a mass noun to a countable noun means. In sentence (13), the same mass noun cheeseNM when changed to a countable form cheeseNC refers to a singular commercial item made of cheeseNM.

"WatersNC" as used in (14) appears to simply be an exceptional case. This is a living usage, I have to regard it as syntactically correct, and it seems to mean "the naturally-occuring waterNM at a specified geographic location"; but it is not consistent with other grammar rules. It may not even really be watersNC, because such waters are not actually countable with a number. Maybe this word is not a plural form of a countable noun at all, but rather a special mass noun that happens to end in "-s." Note that it would also be acceptable to substitute "the polluted waterNM," but we cannot say this:

(15) *Dave fell in the three polluted watersNC of the Love Canal Superfund Site.

It's sometimes possible to go in the other direction, using a countable noun in a mass way. Normally, this is done for small, numerous things, if it's more convenient to talk about them in terms of units of measure rather than literal count. The plural form of the countable noun is used. It seems not to be a very strong change, though: this case may be better understood as simply one of the ways countable nouns are allowed to be used, rather than a real transformation from countable noun to mass noun.

(16) It was more fun than a barrelNC of monkeysNM.

(17) Waiter! I'll have a poundNC of chicken wingsNM, please.

There would be a specific integer number of monkeys or chicken wings involved in each sentence, but we are referring to them by weight or by volume instead, and those are continuous non-integer measurements appropriate for mass nouns. Note that the meanings of these nouns have not changed much because of the special usage: a chicken wing is still a chicken wing, whether by count or by weight.

The case of a little lamb

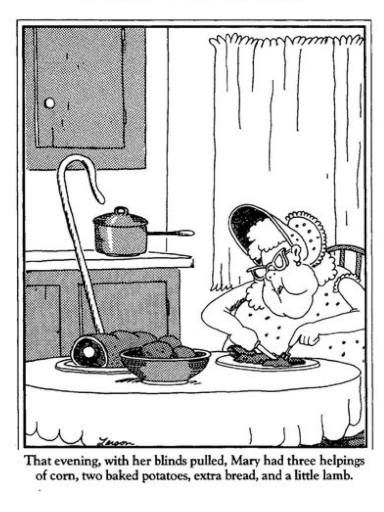

Consider this Far Side cartoon.

In order to be funny, the joke depends on ambiguity in the language. Gary Larson has constructed a situation where the same surface realization of language can be interpreted in two different ways for two very different meanings. It's not only a semantic difference; the way the sentences would be parsed is (at least in many grammars of English) different.

(18) Mary had a little lambNC.

(19) Mary had a little lambNM.

There are multiple differences between the two sentences (18) and (19) even though if not for my subscripts they would look identical. What I call the surface realization of the sentences is identical. The verb "to have" means either "to own" or "to eat." The words "a little" could specify a small amount of the mass noun lambNM or they could be the article "a" and the adjective "little," both attached to the countable noun lambNC and independent of each other. But the biggest and most important difference is that a lambNC (countable) is likely to be understood as a live animal, and that is different from lambNM (mass) which means the meat of such an animal after killing it.

The important thing to note regarding Mary's little lamb is that it may not be obvious whether a word is being used as a countable or as a mass noun, and the difference may have far-reaching effects on meaning. We need to be aware of which form we are using when we use nouns that may have both mass and countable forms.

The cases of "data" and "lego"

It's relatively uncontroversial that at one time standard English included a word "datum" which meant an item of specific information such as a measured value of something, and that was a countable noun (datumNC) which had the plural dataNC. Changing -tum to -ta to form the plural is not the most common rule for pluralizing English words, but is inherited from Latin and used for many Latin-origin words in English.

That time was before the ascendancy of computers, and there came to be a need for a word to refer to the information stored and processed by computers. For better or for worse, the word "data" came to be used to refer to this information. Computer data in present-day usage is a mass noun dataNM, and this usage by now overwhelmingly dominates the older usage of dataNC and datumNC as a countable noun pluralizing by an uncommon rule.

Attempts to use "dataNC" as a plural, especially for things that are processed by computers, have become at best archaic, and usually simply incorrect. Some style guides still endorse dataNC but only if the writer is willing to use datumNC and dataNC consistently throughout a piece and expunge all references to dataNM - which is usually impractical, and nearly always ends up sounding forced when attempted.

(20) We collected ten terabytes of dataNM on piracy and global climate change.

(21) *These dataNC on piracy and temperature indicate a strong correlation.

DataNM behaves like a substance of which there can be more or less of it measured with units of measure, and not like individual objects of which there can be one or two. When one looks at the usage of a hard disk drive, it is expressed as a percentage (a real number), not a count of *"how many dataNC" are stored on the drive. In an arcane technical sense of interest only to specialists, dataNM may have a natural unit of measure (bitsNC), but bitsNC are unfamiliar to most people; even specialists refer to counting bitsNC when to do so is appropriate, not to counting *dataNC; and information theory opens the door to the existence of continuously variable fractional bits anyway. The earlier meaning of datumNC would now be most likely called a "recordNC," "rowNC," "measurementNC," or by some application-specific term, and those pluralize with "-s" as typical English countable nouns.

The word datumNC is still used in some specialized technical contexts, but its meaning has changed and now depends on the technical application. It has fallen completely out of use for the general masses of information now referred to as dataNM. For instance, in geographic information systems a datumNC is a special and singular measurement that officially establishes the origin of a coordinate system, such as the North American Datum of 1983. In computer-aided design and manufacturing a "datum plane" may refer to a place from which the distances and locations in an object are defined, in a usage similar but not identical to the geographic case. Sadly, these specialized technical meanings of datumNC have led to a need to pluralize that word too, and the plural can't be dataNM anymore because that has become a mass noun referring to something else.

(22) This GIS softwareNM can convert among six different datumsNC.

Although it sounds horrible, datumsNC is best usage in this kind of specialized technical context. Writing "data" there would not be acceptable, not as a countable noun nor even with a unit of measure to satisfy the syntactic requirement of using a mass noun, because either way "data" describes a much more generic concept, not specifically the plural of geographic coordinate reference points. Vaguely related: I've witnessed attempts by well-meaning editors to miscorrect "dynamical" to "dynamic" in physics, and "memoization" to "memorization" in computer science. These also are technical terms that lose their important specific meanings when changed to the better-sounding similar words from ordinary language.

Now, what about "lego"? In international standard English, "lego" is best used as a mass noun. Note the use of a unit of measure ("piece") in (24).

(23) The children built a house out of legoNM.

(24) I stepped on a piece of legoNM.

Except maybe in some US regional dialects (and I remain unconvinced of that), "lego" should not be a countable noun.

(25) *The children built a house out of legosNC.

(26) *I stepped on a legoNC.

Lego System A/S doing business as The Lego Group, owner of the trademark, tells people that the "correct" way to refer to their product is to write the name in all caps and use it as an adjective (*LEGO™A). However, practically nobody really uses it that way except The Lego Group's marketing department and some nerds on Wikipedia. The adjective cannot be regarded as correct in the sense of reflecting what is really done and accepted as standard by ordinary people who use the language carefully.

(27) *The children built a house out of LEGO™A bricks.

I think the origin of the official request is in the combination of two factors: 1. careful users of standard English agree that "lego" shouldn't have a plural form (so it can't be a countable noun); and 2. many users of English don't understand that nouns other than countable nouns legitimately exist (so we are forced to the conclusion that it can't be a noun at all). Using it as an adjective is not correct, but given that adjectives don't pluralize in English it creates results as close as possible to the correct ones without requiring The Lego Group to explain the concept of a mass noun to an unreceptive audience.

It's easy to get into fights online over the words "data" and "lego," and something noteworthy happens in such fights: those who are wrong often don't take a position like "there are countable nouns and mass nouns, and 'data' is one of the countable nouns," nor the same thing for "lego." Instead, they often take positions like "the idea of a 'mass noun' is nonsensical and no such nouns exist." Examples of popular mass nouns, such as "water," or references to academic and pedagogical literature on the existence and correct usage of mass nouns in general, have no effect on this position. There is no real discussion of which kind of noun the word in question might be; instead the "discussion" becomes whether there are different kinds of nouns at all; and it's not much of a discussion because evidence has no place in it. It's like a mental blind spot: a deep and irremediable inability of some persons to understand one specific concept. And as readers of this Web log probably know, I find such blind spots fascinating.

The case of Japanese nouns

It may be instructive to consider the different way that nouns work in Japanese syntax.

(28) 山田さんが、二つのリンゴを食べました。

Yamada-san ga, futatsu no ringo wo tabemashita.

Yamada Mr. [subject marker], two items of apples [object marker] eat [past tense polite form].

Mr. Yamada ate two apples.

One cannot correctly say *"二リンゴ" (ultra-literally: "two apples") here, just as one cannot correctly say in ordinary contexts of English *"two gasolines." Japanese grammar requires inserting the counter word "つ" which functions like a unit of measure, and the small word "の” which has a meaning similar to "of," to obtain "二つのリンゴ" (ultra-literally: "two items of apples"); as one might say "two litres of gasoline."

In Japanese there basically are no countable nouns. Nouns (other than proper nouns, such as people's names) all require this treatment of using a counter when one wants to say anything about the quantity, like mass nouns in English. The nouns do not have separate forms for plurals. Nouns without counters simply do not specify how many or how much is meant - and nouns are often left in that state when the quantity is not the point the speaker wishes to convey, or is obvious from context.

(29) 山田さんが、リンゴを食べました。

Yamada-san ga, ringo wo tabemashita.

Sentence (29) (without "二つの") might often be translated as "Mr. Yamada ate an apple," which in English specifies the quantity of one, because of an assumption by the translator that exactly one at a time is the way people usually eat apples. But if there were any reason to care about the quantity, someone reading the Japanese sentence would understand that it does not really say how many and it would still be true whether Mr. Yamada ate one, two, five, or only part of one apple. It just says he ate some unspecified quantity of apple-stuff.

These Japanese sentences do not specify gender, either - we don't know that it is not "Ms. Yamada" all along, and the translator must either make an assumption, get that information elsewhere, or "play the pronoun game." There is a syntactic requirement in English to supply gender information in the honorific title that would not normally be included anywhere in this Japanese sentence. It also goes the other way, as in the following two sentences, which are different in Japanese but hard to translate to English in any way that would convey the difference short of adding notes about the syntactic politeness level.

(30) 山田さんが、二つのリンゴを食べた。

Yamada-san ga, futatsu no ringo wo tabeta.

Mr. Yamada ate two apples and I am speaking informally.(31) 山田さんが、二つのリンゴを食べました。

Yamada-san ga, futatsu no ringo wo tabemashita.

Mr. Yamada ate two apples and I am speaking formally.

The important point here is that distinctions which exist and are important in one language's syntax need not exist in another, and may disappear or may be invented in translation.

I think that even when working within a single and native language, language users may be not consciously aware, but still unconsciously aware, of distinctions between ways of using words that exist in the syntax of their own languages. We are still translating when we translate ideas in our own heads into words to say to another, and then those words back into ideas. Confusion over syntactic distinctions creates accidental misunderstandings and can be deliberately abused to manipulate people. Becoming consciously aware of the less-obvious syntactic distinctions is useful in understanding communication and resisting manipulation.

The case of "privilege"

Here are two quotes from great literary works.

Privileges eh, C.C.? It does seem like The Cheat is overdue. Let's see, the last time I upgraded his privileges was when I reinstated his bathroom privileges; which he had previously abused. Let's see when he's due for an upgrade.

- Strong Bad, Strong Bad Email #74, "privileges"

You will observe, instead, a mathematically smooth function, a steady profit accruing to one group and an equally steady loss accumulating for all others. Why is this, professor? Because the system is not free or random, any mathematician would tell you a priori. Well, then, where is the determining function, the factor that controls the other variables? You have named it yourself, or Mr. Adler has: the Great Tradition. Privilege, I prefer to call it. When A meets B in the marketplace, they do not bargain as equals. A bargains from a position of privilege; hence, he always profits and B always loses. There is no more Free Market here than there is on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

- Hagbard Celine, Illuminatus!, Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson

Strong Bad gives The Cheat new "privileges," notably including use of the crisper drawer (but not for sleeping), and that's just cute. Hagbard Celine's idea of "privilege" seems to be something far more sinister. And yet they're both denoted by what seems to be the same word: "privilege." What is going on here?

It's simple if one paid close attention to the syntactic distinction I wrote about above. There are really two different nouns here that only happen to be spelled the same. "Privilege" is a case where the countable and mass nouns of the same spelling are importantly different. There is privilegeNC, the countable noun; note the clue that with privilegeNC one can write "privileges," the form actually used in my quote from the Strong Bad Email, and that must be the privilegeNC form because only countable nouns have plurals. The Cheat can have a privilegeNC, or maybe two privilegesNC. Then there is privilegeNM, a mass noun. There can be no, some, or greater or lesser amounts of privilegeNM but there can't be one or two of it absent a unit of measure, and it has no plural form. Strong Bad gives The Cheat new privilegesNC; Hagbard Celine thinks the Great Tradition of both East and West is well-described as privilegeNM. They are different things.

One of the important, defining features of a privilegeNC is that it must be earned, and then one can be due to receive it, as The Cheat is due for an upgrade in his privilegesNC. PrivilegesNC exist at all only because of some agreed-upon framework and standard of fairness. It can be inferred from the animation in which that quote originated that The Cheat has spent a long time collecting points to become a member of the Medallion Gold Plus Club, and he now deserves new privilegesNC. PrivilegesNC are easy to understand as morally justified and right, as part of their definition; an unearned privilegeNC may be imaginable but is not a good and proper example of the type. One of the most common reasons people talk about privilegesNC at all is to draw a contrast between them and "rightsNC." Strong Bad could meaningfully warn The Cheat:

(32) Remember, the crisper drawer is a privilegeNC, not a rightNC.

The privilegeNC of the crisper drawer is something one must earn, and might well also lose by misconduct, as The Cheat once lost his "bathroom privilegesNC"; privilegesNC go hand in hand with responsibilitiesNC. A rightNC, in contrast, does not need to be earned and (as a matter of justice, if not practical fact, and again assuming good and proper examples of type) a rightNC cannot ever be lost or taken away.

Compare that concept with the concept of privilegeNM, which appears to be opposite in important ways. PrivilegeNM is not earned or fair. In fact, the idea of privilegeNM being unearned and unfair seems to be fundamental to its definition. Anything one could gain by honest personal work or by fair trade among equals is far outside and basically opposed to the concept Hagbard Celine is talking about in my quote. That concept is all about arbitrary enforced status for those who do not deserve it; and if such a thing should be possible, any morally good person who somehow happens to have privilegeNM ought to be ashamed and repentant. Morality in the book Illuminatus! is complex but it would seem natural to many people that privilegeNM as described in that quote is something evil and wrong. In religious terms, it is sinful, but necessarily as a form of original sin because it is inherent in the person and did not come from anything he* did by volition.

(* Why did I write "he" here?)

One could easily work hard like The Cheat all one's life to earn privilegesNC at great personal cost. One could easily listen to discourse like Celine's, be horrified by it, and pledge to spend one's life fighting against privilegeNM. What happens when these two meet?

One will hear the other say "I have devoted my life to taking away from you that which you have rightfully earned." The other will hear "I seek to preserve for myself an unfair and wrong advantage that I did not earn." These are not two different opinions about the moral status of one thing. These statements are about two different things.

Unless both sides fully understand that privilegeNM and privilegesNC are really different, not the same and not even a little bit comparable no matter how similar the words may look on paper, and this critical difference is indicated primarily by the difference in syntax when talking about the two, this meeting is not going to go well for anybody. And it's quite easy to confuse two words that look the same, sound the same, and differ by subtly different syntax rules that many users of English know intuitively but would not be able to explain clearly or consciously.

We are much quicker to conclude that someone else is evil than to conclude that the same person genuinely believes a totally different definition of an important word - and motte-and-bailey tactical redefinitions often applied to words like "privilegeNM" do not improve the situation at all. Such tactics demonstrate that their users cannot be trusted to talk honestly about definitions, or listen honestly to differing definitions, and make impossible any joint elucidation of differences like the difference that exists between a privilegeNC and privilegeNM.

Verbs intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive

In English, it is a basic requirement that every sentence has a verb and the verb has a subject. This requirement is strong enough that in sentences with no natural subject we must add an extra word to fill the grammatical role.

(33) It is raining.

What is raining? "It." Nothing specific. We just needed to put a word there to satisfy the grammar rule.

Imperative sentences are a major class of exceptions to the rule that verbs must have subjects: we leave out the subject, which is then implied to be "you," to show that the sentence is a command.

(34) MoveVT that thing, and that other thing.

Who moves the things? Whoever the command is directed to - the grammatical second person, "you," which is omitted from the sentence in order to mark it as an imperative.

There are also a few exceptional idiomatic sentences that have a verb with no subject, notably these two. They look a lot like imperatives, but are not exactly. At least in (35), the omitted subject appears to be "I."

(35) ThankVT you.

(36) FuckVT you.

English sentences without verbs may occur either in special idiomatic constructions, or as fragments, arguably not really sentences, used to answer questions.

(37) The more, the merrier.

(38) What's in the box?

Stuff.

But ordinary sentences that are not special in these kinds of ways really need to have both verbs and subjects.

Verbs can have objects, too. In fact, a verb can sometimes have two objects. But it also might have no object. The object is not a required part of all sentences in general, as the subject is. An object might be required in a sentence; but it depends on the verb. Verbs can be classified as intransitive, transitive, or ditransitive, for the verbs that take zero, one, or two objects respectively. I will say "transitive" for verbs that take exactly one object; some might prefer to call those "monotransitive" and use "transitive" to refer to verbs taking at least one object, thus including ditransitive verbs within the category of transitive verbs. I know of no tritransitive verbs in English. Some verbs strongly prefer one of these categories; others can be used in more than one way; but when what looks like the same verb is used with different numbers of objects, often its meaning changes significantly.

(39) Alice calledVI. subject intransitive verb

(40) Alice calledVT you. subject transitive verb object

(41) Alice calledVD you a cad and bounder. subject ditransitive verb direct object indirect object

Sentence (39) might mean that Alice made contact by telephone or (although this may be archaic or dialect-specific) that she arrived in person for a visit. Sentence (40) probably refers to a phone callNC and not an in-person visit, but it could also refer to shouting. Sentence (41) describes a completely different kind of action: Alice made a personal comment about you, maybe spoken or in writing. Maybe she even calledVI just for the purpose of callingVD you a cad and bounder.

If we look at a word spelled "called" in isolation we have no way of knowing which of these it might be. I have marked them VI, VT, and VD, for "verb, intransitive"; "verb, transitive"; and "verb, ditransitive," to make the distinction clearer. It's easier to understand that "to callVD" has a completely different meaning from "to callVI" if we can see the subscripts.

Just as a noun may change its meaning significantly when used in a mass or countable way, so too may a verb may have related but significantly different meanings when used in a transitive or intransitive way.

(42) Bob drankVT waterNM.

(43) Bob drankVI.

The verb to drinkVT in (42) refers to the concrete physical act of consuming any liquid, in this case waterNM, probably on one specific occasion. To drinkVI is a more abstract concept: in most contexts it would be understood from (43) that Bob had the habit of frequently drinkingVT alcoholNM, probably as a matter of addiction, and the sentence is not referring to just one specific occasion. And this is a common pattern: when a transitive and an intransitive verb have the same spelling, quite often the transitive verb is talking about something more concrete and the intransitive verb is talking about something more abstract. The pattern may arise simply because concrete, specific events need more information to be completely specified, and having an object for the verb provides more bandwidth for information in the sentence than not having an object for the verb.

If transitive and intransitive verbs have different meanings, what happens when it's not clear whether a given verb is being used in the transitive or intransitive way? What happens when someone tries to use both verbs, with care to distinguish them, and someone else expects there to be only one verb with one meaning in play?

Ditransitive verb usage may be another blind spot: "deem...as"

As with mass nouns, some users of the English language have trouble using ditransitive verbs correctly, and many seem not to be consciously aware of the existence of ditransitive verbs at all, even if they may be unconsciously able to sometimes generate syntactically correct sentences using these verbs. I've lost count of how many times I've edited the "deem...as" construction in particular out of Wikipedia, student essays, etc.

(44) *The court deemedVT the document as libellous.

(45) The court deemedVD the document libellous.

It's relatively easy to see that (44) is wrong and (45) is right; but not everyone who agrees to that can explain exactly why. You deemVD something something; you don't *deemVT something as something. There is no *deemVT.

But if one does not have a clear conscious understanding of the existence of ditransitive verbs in general, one might look at "deem," assume that it is correctly *deemVT by analogy with other somewhat similar verbs, and then (correctly, for transitive verbs in general) assume that in order to attach a second thing to it after the first object, one must use a preposition. I don't know why these people always seem to want to use "as" in particular and not some other preposition. Consider the following sentence, which looks similar but is correct because it uses the different verb condemnVT which takes one object but can take an additional argument tacked on with "as." I am saying "argument" instead of "object" to emphasize the grammatical difference.

(46) The court condemnedVT him as a traitor.

One important difference is that deemVD needs a second object. One cannot correctly giveVD it just one.

(47) *The court deemedVD the document.

With condemnVT, one can also giveVD the verb one object and nothing more, or even giveVD it more than one additional thing after the object, using appropriate prepositions to attach them.

(48) The court condemnedVT him.

(49) The court condemnedVT him to the firing squad, as a traitor, upon consideration of the evidence, in a carefully-written decision.

The case of "change"

In a couple's therapy session:

(50) You should stop trying to change your partner.

(51) She should stop being afraid of change!

At first glance it might seem that one of these sentences is a response to the other. Both appear to be talking about the same thing - they use closely parallel words, in particular "change." But are these two sentences really talking about the same thing?

(50) You should stopVT tryingVT to changeVT your partner.

(51) She should stopVT beingVT afraidA of changeNM!

Note the subscripts. It's not the same "change" in the two sentences. The word "change" has fundamentally different meanings keyed to the different syntactic roles that this sequence of six letters may play in a sentence.

I can think of at least:

- changeNC - a specific concrete instance of something being different between an earlier and a later timeNC

- changeNM - the general abstract concept of becoming different with the passage of timeNM

- to changeVT - to cause a changeNC in someone or something

- to changeVI - to undergo changeNM

Of course there are other possibilities too, like the changeNM meaning "coins" that a beggar might ask for in the street, but the four above are the ones that appear to be most strongly linked to each other; and they still differ greatly among the noun and verb forms and the different kinds of nouns and verbs. Note that changeVT and changeVI are opposite in one important sense. In one the verb's subject undergoes changeNM (and there is no object) and in the other, the verb's object is the entity that undergoes a changeNC.

There are further issues which we can also notice by looking closely at the syntax of these sentences.

(50) You should stopVT tryingVT to changeVT your partner.

The most important verb in this sentence is not to changeVT but to tryVT - emphasis on the attempt, which (we can guess from elementary psychology) is very unlikely to be a successful attempt resulting in any real changeNM. To tryVT to changeVT is a different meaning from to changeVT as in the following sentence, which represents one of the concepts under discussion.

(52) He changesVT his partner.

But to changeVT - a transitive verb taking an object, describing an action done by someone to someone else as contemplated in (50) - is further different from to changeVI, an action done by one agent unilaterally. The difference between the transitive and intransitive verbs in this case corresponds to a great leap in the meaning.

(53) She changesVI.

What he does in (52) is very different from what she does in (53) despite being represented by the same sequence of letters.

But even this leap does not bring us into the conceptual space of (51) because (51) does not use "change" as a verb at all, transitive or not. Instead it's using it as a mass noun.

And finally, there's a leap from "changeNM" to the phrase "afraidA of changeNM" where the key word is "afraidA" (an adjective), not any verb, noun, or other form of "change" at all.(54) We're talking about her changeNM, not his.

(51) She should stopVT beingVT afraidA of changeNM!

The sentences (50) and (51) superficially appear to be in the same conceptual space because both contain "change"; but one is changeVT, the other is changeNM, and those words are not even really the key words in either sentence. From (50) to sentence (51) there are fully four important conceptual gaps: tryVT (50) to changeVT (52) to changeVI (53) to changeNM (54) to afraidA (51).

If these people treat (51) as a meaningful response to sentence (50) they will quickly become bogged down in mutual incomprehension, because there is little or nothing that can usefully be said about tryVT that will be applicable to afraidA, nor vice versa. Even if they focus in on "change" (eliminating two of the conceptual gaps), the verb to changeVT (to cause a changeNC in someone or something) is so far away from the noun changeNM (the abstract concept of evolution over time) that little or nothing can be said about one that will be applicable to the other. The most we can hope for is that maybe the therapist was trained to notice this distinction - because ordinary people certainly are unlikely to do so.

Cases like this where one side uses superficially similar words in different ways to convey a different meaning from another side, can be created artificially for tactical purposes. Recognizing them is important as a way of defending against such misdirection. But they can also arise "innocently" just because people happen to have made different assumptions in the past. For that reason, it's useful to recognize them and talk about them even in non-adversarial contexts.

I've described two important distinctions in English syntax, that between countable and mass nouns and that between intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive verbs. I've gone through some examples of each distinction and the way that words which seem identical on the surface can have different meanings depending on these syntactic differences. I'm hopeful that by making such issues clearer we can all understand each other better.

1 comment

Kit - 2018-09-24 11:10