Scarcity, abundance, and lost careers

Mon 29 Nov 2021 by mskala Tags used: philosophy, employment, academicHow should institutions make hiring and promotion decisions, in theory? How do institutions make such decisions, in actual practice? What happens, and what should happen, when someone's career is interrupted? Is it possible to restore an interrupted career, and should that be done? What happens to institutions when society overproduces, or underproduces, elite individuals? This article looks at ways to understand these questions, starting from an historical episode.

The Dreyfus Affair

In 1894 a young officer of the French Army named Alfred Dreyfus was accused of selling secret information to the German military. He was convicted by a court-martial, sentenced to life exile, and imprisoned in horrific conditions on Devil's Island, off the coast of French Guyana. The evidence against him was flimsy to begin with, and almost immediately was discovered to be fabricated; but senior staff in the Army, apparently hoping to avoid the embarrassment of admitting they had made a mistake, attempted to cover up the fact that they were punishing an innocent man.

Dreyfus was Jewish, and that made him appealing as a scapegoat. Many in the Army and in the public were willing to consider him automatically a likely traitor just because of his heritage. These events took place long before the Second World War and the existence of Naziism. Anti-semitism as a political position was certainly abhorrent to very many people in France at the end of the 19th Century, but not to everybody; at that time it was still within what we might now call the Overton window, of political positions that could safely be taken in public discourse. There was even a "National Anti-Semitic League of France" founded in 1889, which was able to openly operate and call itself that.

In the years following Dreyfus's conviction, his family's efforts to clear his name gathered public attention and became inextricably linked with the left/right political conflicts that existed in the French Third Republic. Whether someone thought Dreyfus was guilty or innocent was not just a question about the facts of one court case. It became a statement of aligning with a side, and of implicitly taking a position on many other issues as well. There was constant newspaper coverage; there were leaked documents and rumours; eventually there were multiple court cases, and tampering with evidence, witnesses, and judges; there were duels fought over personal conflicts connected with the situation; there were suicides of important figures and suspicious-looking accidental deaths; violent street demonstrations of both sides occurred all over France and sometimes internationally; scientific and pseudoscientific questions related to forensic examination of documents became significant (see Appendix A); and so on. The 12-year period of political controversy and social upheaval set in motion by the original accusation became known as the Dreyfus Affair.

In July 1895, an officer named Georges Picquart (then a major, promoted to lieutenant-colonel very soon after this appointment) became head of the "Statistics Section," which was the deliberately misleading name of the Army intelligence department. Picquart held anti-semitic political views; initially believed Dreyfus's guilt; and had been a witness at his first court-martial. However, in this new position, Picquart became aware that the espionage for which Dreyfus was imprisoned was still ongoing, indicating that at the very least, Dreyfus could not have been the only traitor involved. Picquart investigated further and found evidence that convinced him Dreyfus had been innocent from the start, and led him to the real spy, a Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy.

Picquart refused to drop the matter after being repeatedly warned away by other officers, who were shielding Esterhazy partly in order to conceal their own culpability. The senior staff conspired to get rid of Picquart, first by sending him to remote locations including Tunisia (a dangerous posting where it seems they were hoping he would be killed), and then imprisoning him on accusations of various offences, including forging documents and leaking information to the newspapers. The process of his formal court-martial was interrupted by a second court-martial of Dreyfus, and by political developments on the civilian side. A bill in the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of France's bicameral legislature as it existed at the time, roughly equivalent to the House of Commons or House of Representatives) aborted all the then-current Dreyfus Affair court cases in an effort to quell the ongoing public uproar. Picquart was released from prison in 1899, but had been forced out of the Army.

Alfred Dreyfus was brought back from Devil's Island in 1899 to face his second court-martial, which revisited the charges in the first one, examining the new evidence of his innocence, but still convicted him a second time. Then he was pardoned by executive action of the government. That meant they were deciding not to punish him any more, without in any official way admitting that he really was innocent. The wording of the letter of pardon signed by the President of the Third Republic made clear that it was a political and not judicial act. Dreyfus was free to re-enter civilian life, but he had no career in the Army anymore, and what he perceived as his family's honour was not restored. The entire situation continued to be a controversial subject of public discourse; the government's attempt to end that was largely unsuccessful.

In 1906, after a further seven years of public controversy, political and legal maneuvering, and the election of a new government more favourable to the pro-Dreyfus side, the civilian Supreme Court quashed Dreyfus's conviction, ruling that all the evidence supporting the initial charges against him had become legally inadmissible by reason of having been fake. The decision was "without reference" to another court, meaning that he could not be subjected to a third court-martial. Dreyfus was disappointed not to have his name cleared by a military court, and the decision without reference put that out of reach; but unlike the pardon, this was an official admission of his innocence. It was considered to restore his honour as an officer and a gentleman, and it meant he could serve in the Army again.

This description is highly abbreviated. There is a lot more that can be said about the Dreyfus Affair and I have focused only on the points that are most relevant to what I want to say about institutions, promotion, and elite production. See the bibliography below for work covering other aspects of the historical events.

The what-if game

Although there's a lot that can be said about the Dreyfus Affair, the point that interests me most is one detail: how the French government and the Army, as institutions, tried to make amends to Alfred Dreyfus for his mistreatment at their hands.

They played the what-if game. Dreyfus had trained for, and was at an early stage of, what ought to have been a career as a military officer that would last the rest of his working life, when the false accusation threw his life off the rails. After five years of torturous imprisonment and seven years of spinning his wheels as a civilian, he'd lost twelve years out of that career. So they attempted to give those years back. They reconstructed the career he might have had if not accused, and they promoted him to the level within the Army that he would have been at if he had served twelve years of a normal career, working his way up through the ranks, instead of what actually did happen.

Or, so they (specifically, the Chamber of Deputies) said at the time. I discuss below whether the promotion he received actually was consistent with the what-if scenario. For the moment, let's suppose the institutions really did in good faith give Dreyfus, upon his exoneration, all the promotions and other status he would have achieved in twelve years of an hypothetical uninterrupted career.

Was that the right thing to do?

Well, we can say he earned it. He underwent hardship for it. As a matter of justice I'd say they owed him at least what they offered and probably a lot more. It is remarkable that he still wanted to serve in the Army after what the Army had done to him; but given that the career of an officer in the French Army really was what Alfred Dreyfus desired, and that career was unfairly taken away from him, from the point of view of his rights as an individual, he ought to be given it back.

Let's do another what-if. Suppose instead of promoting Dreyfus, they just allowed him back into the Army at the level he had been at when he left. That was the level of someone who had recently completed a program in a military graduate school before joining the General Staff for a two-year probationary period of on the job training, which was almost completed at the time he was accused. If he picked up at that point, exactly where he left off after twelve years, it would make him probably the oldest new trainee in the General Staff's history. Not exactly an auspicious place to launch a great subsequent career. Even if he never faced any age discrimination, he would be unlikely to make an impressive lifetime achievement record before he retired simply because he wouldn't have time. They would be giving him employment, but closing the doors that had been open before him twelve years earlier. So the scenario of picking up just where he left off, would not really restore what was lost.

But being a higher-level officer is a job with duties and responsibilities. Was he really fit to do that job? Normally, someone serving at the level where the Chamber of Deputies said it would put Alfred Dreyfus, would have had twelve years of experience that he did not have. The officer who went through the normal course would have been commanding troops, fighting battles, making executive decisions, or otherwise fulfilling the duties of an Army officer all those twelve years, acquiring the skills that would make him fit for promotion. Dreyfus instead had twelve years experience of nearly dying from tropical diseases, teetering on the edge of sanity in solitary confinement, and getting caught up in a public scandal. It might be said that he had a twelve-year gap on his resume, which would not cease to be true just because he got a new job title.

Suppose you are an enlisted soldier about to go into a battle where you may well die. Do you want to be commanded in that battle by an officer who has spent his whole career up to this point actually doing the job of an officer? Or do you want to be commanded by a man who is the same age and official rank, and who morally deserves to be considered as having the same number of years of experience; but who did not actually do the job of an officer for most of his years?

Furthermore, suppose you are an officer even higher on the chain of command than Dreyfus. You are choosing who will lead a unit on a difficult mission. You need an experienced and skillful officer. Will you choose the man who has twelve years of experience, or the man who morally deserves to be considered as having twelve years of experience? Bringing Dreyfus back into the Army as the oldest General Staff trainee ever, would not have been right; but bringing him back as the least experienced higher-level officer ever, might not be a lot better.

With the possibility that those above him might treat his deemed experience as less than entirely real, even just from Dreyfus's own point of view the promotion might not be doing him a great favour. His future opportunities might not be all he could hope. Would he be treated as an equal by other officers who had advanced to the same rank, but in the usual way? Everybody would know his promotion was honorary and different from the others. The Army as an institution might well perceive him as less qualified than most officers at the same official rank, and it could impair his ability to advance any further after this one special promotion. And this might not be only a matter of perception. It could be objectively true that his ability to do the job of a higher-level officer would be less than that of someone who had followed a normal career path to high rank.

Should a high-ranking officer be deserving, or skilled? Is it more important for the soldiers of the Third Republic to die waving bayonets for honour, Marianne, and liberté égalité fraternité; or to win battles and achieve strategic objectives? Should their officers be honourable, or effective? Is that a false dilemma after all?

These questions should not be answered too quickly.

Consider Picquart. He held anti-semitic political views, but ended up taking the Jewish side in the Affair, losing years of his own career and risking his life, because that was the honourable and morally imperative thing to do - a mitzvah even if he would not have used that word. Maybe his dedication to truth and duty was the right stuff for a senior officer, and actually more important in determining his suitability for promotion than years of experience would be. Soldiers deeply committed to honour, Marianne, and liberté égalité fraternité would rightly prefer to be led by such a man. The abstract principles at stake here really do matter. Without them, the Army might win a battle only to have it mean nothing.

The way I've told this story, it seems the argument is very strong that promoting Dreyfus and Picquart was a bad thing, an example of irrational behaviour on the part of the institutions involved. But I deeply distrust that quick assessment - as I've said, the questions should not be answered too quickly. I feel like I want to say that it was actually a good thing for the Army to promote these men. Working through why such a conclusion would seem appealing to me leads to two distinct lines of thought: two different theories of what promotion might really be for and how an institution should handle it. The two theories have opposite conclusions. Either of them might be right. Importantly, neither of them is universally right for all institutions at all times. One might have been right with respect to the French Army in 1906, and the other with respect to, for instance, a North American university a century later. It all just depends on the prevailing conditions of the moment.

Scarcity

Suppose a fly upon the wall (une mouche sur le mur) at the French Army headquarters overhears a briefing on the general subject of promotions. It might run something like this, translated.

Serving France as a high-ranking officer is a difficult job for men of the highest skill and experience. Good candidates for promotion are scarce. Most lower-ranking officers are not good enough to be promoted higher. Promoting one who is not capable of doing the job has disastrous consequences. We must find the best candidates, and only the best, objectively evaluating them. We must train each candidate to the highest standard he can reach, and be sure not to lose any. When we go looking for someone to fill a position, there are so few applicants who meet even the minimum objective requirements, that we may be forced to leave the position unfilled. Of course, we cannot promote anybody for reasons other than his actually having the necessary skill and experience, because the Army needs the very best men. Vive la France!

An institution operating in conditions of scarcity has more high-ranking positions requiring skill and experience than there are qualified promotion candidates who can properly fill those positions. An institution operating under a theory of scarcity is one that perceives the conditions of scarcity and responds accordingly.

By scarcity I mean scarcity of qualified candidates, as a proportion. There are likely plenty of lower-ranking candidates the institution could at least consider promoting, but almost all the candidates are bad. It is difficult to find the few who are really able to do the more difficult work of higher-ranking positions.

The theory of scarcity has assumptions built into it about the shape of the problem it is describing. The core of scarcity theory is the institutional belief that there are not enough suitable candidates for promotion. In order for that to be a meaningful statement, and for the institution to be able to operate at all, we also must believe other propositions about it being meaningful to describe a candidate as suitable for promotion, or not; and what it actually does mean for a candidate to be suitable for promotion.

Scarcity theory says skill is a quantity. Some candidates have more or less skill than others. A candidate who can do a certain difficult job, at all, necessarily has at least a certain amount of skill; and a candidate with more skill can do that job better, or can do a more difficult and therefore higher-ranking job. Difficulty of the work increases with rank of the job as a matter of definition, not only an observed fact that might happen to be true.

Skill is an objectively definable quantity both for candidates and for the work they do. It may possibly be hard to measure skill, and it may be multidimensional and therefore somewhat harder to compare between individuals, but in fact it usually is easy to measure skill, and whether we can measure it or not, a single correct answer exists to the question of how skilled a candidate is along a given dimension, or how much skill a job requires. Given two candidates, it is meaningful to say "this one is more skilled, that one is less skilled"; and fine gradations of skill exist, so that we will seldom to never be confronted with two candidates and no way to prefer one over the other. Given two positions, it is meaningful to say "this one requires more skill than that one." It is a matter of objective fact which one is which.

With a scarcity of candidates who can safely be promoted to the higher-ranked positions, the institution cannot afford to lose any. The institution in scarcity will offer incentives for everybody to advance as far as they can. The high-ranking positions in an institution operating under scarcity are likely to be well-paid and will certainly be high-status, that is, positions of honour. The institution depends on keeping everybody desirous of those positions.

It is important not to promote anybody who does not meet the necessary objective standards, even if that means positions go unfilled. Such a person could cause damage directly through incompetence in doing their difficult job, but their promotion also indirectly damages the system and the ability of the institution to get the best work from the best candidates, by harming the honour and prestige of the higher ranks. One unqualified individual at a high rank creates the suspicion that standards in general are too low and anyone else at the same rank may be similarly incompetent.

Scarcity means that most individuals at a given rank will be ones who only just barely met the criteria for that rank. Individuals with significantly more skill would be promoted further instead of stopping at their current rank; and individuals with more than the minimum skill for their rank, but not enough to reach the next rank, will be a small proportion because of the overall bottom-heavy nature of the assumed power-law distribution. In any interval of skill levels, most of the population who fall within the interval will be near the bottom. The point that most individuals under scarcity theory end up in ranks for which they are just barely qualified is basically the well-known Peter Principle, although derived from different assumptions.

Beyond being objectively definable, scarcity theory holds that skill can be increased by experience and training. There might be some variation in genetics or similar that might cause individuals to start at different points, or even possibly limit their eventual advancement, but skill primarily comes from experience and training - not from identity. The institution doesn't and shouldn't care who you are. What really matters is your experience and training. Scarcity theory says that good candidates for promotion are made, not born.

Objectively definable skill means it should be possible to write down a precise criterion for a candidate to be eligible for each rank, and an institution that follows the theory of scarcity is likely to indeed write down such criteria. The possibility of training individuals to a higher skill level means training itself can be a way of measuring skill: the objective criteria for promotion can often be along the lines of "You must have completed this course to qualify for this rank," maybe with some kind of a threshold on the final exam score or similar. Credentials and certificates are useful and often used by institutions under scarcity, as a way of abbreviating job requirements into criteria that are easy to define concisely. The idea that skill increases with experience also leads to easily measured objective criteria based on length of experience, as "You must have held this rank for this many years to move up to the next rank."

My paraphrased criteria are stated in terms of necessary conditions for promotion, not sufficient conditions. Just because you completed the required course does not, on the surface meaning of the words, entail that you really get the rank. If there are two applicants for one position, both having passed the training course, the institution will choose the best one - and it is assumed that there is really such a thing as "the best one." But such cases do not occur much in scarcity, because there are not enough candidates passing the course in the first place. All the ones who do meet the objective standards actually will get the rank if they want it. In scarcity practice, the necessary conditions become sufficient conditions.

Scarcity of qualified candidates implies enough high-rank positions exist for all of the few who are qualified, so one of the important incentives the institution can offer to lower-ranking individuals is a credible promise of career advancement conditional on meeting the published objective criteria. If you get the training, accumulate the experience, and take the tests and get high enough scores on them, then you are really allowed to expect the honour of promotion.

An important value embedded in scarcity theory and underlying the promise of career advancement is the value of procedural fairness. For an institution in scarcity there are always rules; the same rules apply to everybody; and everybody agrees that it is important and good for the institution to work that way.

Abundance

Another fly upon another wall, in some other hypothetical French Army headquarters, might overhear a very different briefing.

Almost all the men serving France as junior officers today could also do the work of senior officers if they had the opportunity. Good candidates for promotion are abundant. We don't promote them all, only because we don't need that many senior officers. That does not mean senior officers have a particularly easy job; only our corps of junior officers is just that good. Furthermore, every rank and even every position is unique. To the extent that some officers are better than others, we cannot predict who will be the best senior officers from their performance at lower ranks. And the difference between a good officer and a better officer is inherently a subjective judgment anyway, that we cannot measure in practice and maybe not even in principle. The ability to be a good senior officer is also not something we can teach. Because almost all candidates are good and our ability to evaluate them precisely is limited, it is inappropriate to waste effort purporting to pick out the very best ones beyond basic competence, which is easy to recognize. Our main problem when trying to fill a position is how to narrow down an unmanageably long list of candidates who are all good enough. It is necessary to apply arbitrary criteria to the list just to reduce its length; and given that necessity, it is appropriate to use promotion decisions for social goals, such as liberté égalité fraternité and justice for society. Vive la France!

When almost all candidates are good enough, and good candidates far outnumber the high-ranking positions into which they can be promoted, that is a factual situation of abundance. As with scarcity, it is possible for an institution to follow a theory of abundance: it perceives the facts of abundance and implements a response appropriate to those facts.

Although abundance is defined as a high proportion of candidates being good enough to serve in high-ranking positions, this theory also holds that the sheer number of candidates is large in comparison to the demand for them. There are so many candidates the institution cannot look carefully at all of them when making promotion or hiring decisions. Fortunately, it does not need to.

The abundance theory comes with assumptions that are to a large extent the opposites of the assumptions in scarcity theory. Abundance theory needs to solve a totally different problem and uses different concepts to describe that problem. Having almost all candidates good enough means that fine distinctions to determine which ones are better, no longer are significant. The concept of skill as a measurable quantity fades away; instead, it will be observed that the remaining differences among individuals, although real and important, are subjective, unpredictable, and do not seem to improve with training. Abundance theory holds that the greatest candidates for high office are born, not made, and also are hard to recognize early.

Job duties still need to be performed, and some people can perform them and others can't. But distinguishing bare competence at the yes or no level is not the problem which needs solving in abundance. The institution in abundance apprehends basic competence as easy to recognize, as well as being plentiful. The institution does not put much effort into defining objective criteria for evaluating basic competence, because that doesn't need much effort. Recognizing truly great individuals as distinct from the merely good enough might still seem like it could be valuable, but abundance theory understands the differences between good and great individuals as fundamentally outside the institution's capability to judge or predict - and therefore counterproductive to attempt.

There may even be a denial of the potential existence of great individuals at all, stemming from a focus by the institution on society instead of on individuals. "Great individuals" is seen as simply the wrong way to think about society and the institution's place within society. Such denial carried to an extreme is diagnostic of the "dissipation" state I will describe later, but even in ordinary abundance it is likely to appear in a less extreme form. Institutions in a state of abundance, especially those like universities whose mission directly includes the formulation of philosophical theories, are likely to adopt philosophical frameworks that deny objectivity as a general principle and in particular its application to evaluation of individuals for promotion or hiring.

Then having determined the non-existence of any important objectively real differences between already good enough candidates, the institution has no reason to measure something that doesn't exist. And even if one might disagree with that determination, the fact that almost all promotion candidates really are good means it is harmless for the institution to deny the existence of job-relevant measurable distinctions. The denial does not hurt the institution at all; they have plenty of good candidates anyway. Institutions in abundance do not need objective criteria beyond basic job duty competence.

Rejecting the comparison between good and better candidates also means a much reduced emphasis on training and experience. Training and the resulting credentials may be necessary to look at as a purely technical matter, but are not seen as the main key to solving the real problems in hiring and promotion. Experience is not highly relevant to promotion because the differences that may still exist among candidates are things they bring with them as parts of their identities, not acquired over time.

The institution in abundance perceives the real problems of hiring and promotion as how to narrow down an excessively long list of candidates, all of whom are good, and more broadly how to use that narrowing-down process to create the best outcomes for the larger society. It cannot promote everybody. It has to reject some. How will it choose whom to reject? Objective skill related to job duties is not a problem that urgently needs to be solved; measuring it may be impracticable anyway; and may be impossible, by philosophical definition. So the institution will turn to solving other problems. Seeing its own mission in the context of the broader society, it will attempt to make its hiring and promotion decisions part of making the world a better place.

Abundance as such does not specify which problems in society need to be solved, only that it is the institution's job to help solve them, whatever they are. In France in the first decade of the 20th Century, political division was high on the list of problems, so the Army would make an effort to demonstrate that its promotion decisions were fair to both sides of the ongoing republican versus nationalist conflict. The Affaire des Fiches of 1900 to 1904, overlapping the later years of the Dreyfus Affair, showed the cost to the Army of choosing the wrong issue. The Army had been maintaining a secret card file on officers, using information collected through Masonic lodges, to keep track of which officers were thought to have republican as opposed to traditional political or religious views, giving promotion preference to the republicans. After the resulting scandal the Army was forced to go to lengths to demonstrate its even-handedness. But even the pre-scandal fiches system fit the typical abundance-theory pattern of using hiring and promotion to solve problems in the larger society. The Army institutionally believed that nationalism was a problem in France that needed to be solved, and - given almost all promotion candidates were good anyway - it chose which ones to promote in such a way as to help solve that social problem. It just made a choice that proved to be unpopular of which social problem it should be helping to solve.

The selection of which bigger issues in particular to address does not come from the abundance theory; only the imperative to use hiring and promotion to address some bigger issues. But the issues selected will often happen be ones that can be cast as some sort of equity, because equity as a general principle is directly supported by abundance theory. The fact of almost all candidates being good enough pushes the institution toward the idea of almost all persons being good enough, and therefore toward adopting more general equity principles.

I wrote that scarcity theory embeds a value of fairness. So does abundance theory. But fairness in abundance is a different kind of fairness from that in scarcity. An institution operating on a theory of abundance will prioritize fairness in the sense of equity, fairness in the results for individuals and for society as a whole. It may be seen as fairness with respect to consequentialist ethics (results-based) or on an ethical concept of virtue (inherent goodness of people), as opposed to the fairness with respect to deontological ethics (rule-based) that is given priority in a theory of scarcity. Objective, written, and general rules of fairness in an institution following abundance are tools for achieving fair results for good people, and if the consistent application of a general rule would conflict with fair results in the case of a good person, then that rule ought not be followed in that case.

More about Dreyfus and Picquart

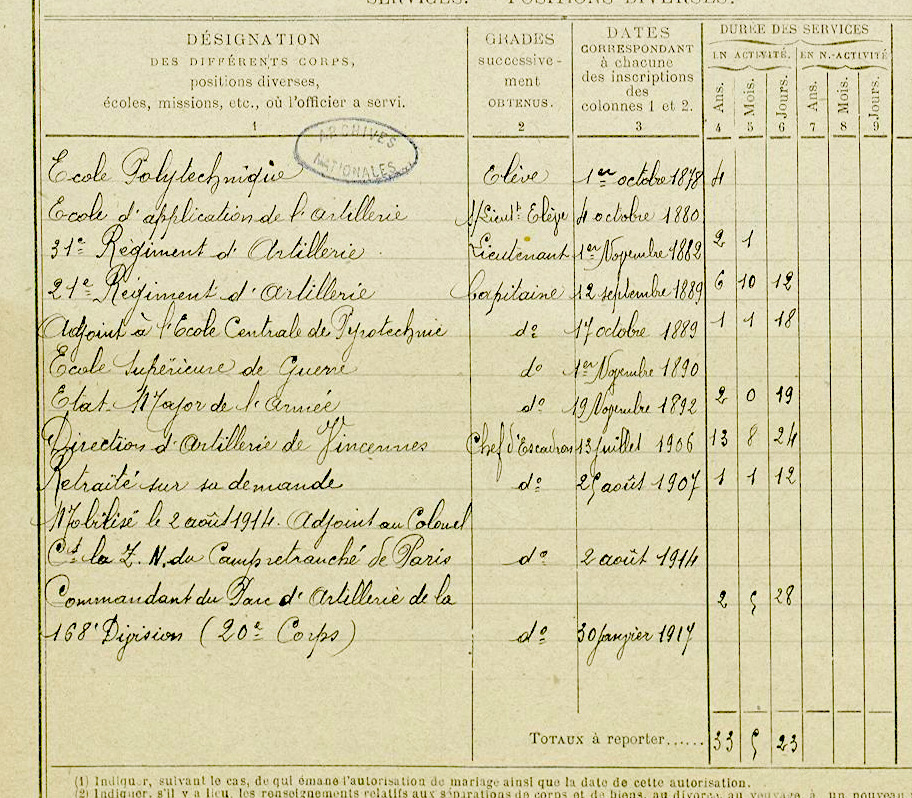

Dreyfus and Picquart were each promoted when they were brought back into the Army, and I am interested in the specific details of how far they were promoted, and why. I'd like to know which of my "scarcity" and "abundance" theories better describes how the institution of the Army handled the situation, and whether or not either theory describes it well at all. Here are some relevant factual points, some of which make the issues I have highlighted less significant in the historical event.

- The decision to promote Dreyfus and Picquart at all was officially made by a civilian political institution, the Chamber of Deputies, which had different priorities from those of the Army.

- The stated intention was to restore their careers: to put these two men where they would have been if the Affair had not happened.

- The call of exactly how far to promote them was made by the Minister of War, Eugène Etienne, who was a career politician and never served in the military himself, but may have had a perspective more focused on the Army's institutional needs than the Chamber of Deputies had as an institution in itself.

- The promotion Dreyfus actually received was only a small one, from captain to major effective on the date of the decision. This may have been the smallest promotion the Army could give and still say it was promoting him at all.

- Although the "what if" question is hard to answer precisely and convincingly, it is clear that the promotion given to Dreyfus was not really big enough to achieve the claimed restorative goal.

- Dreyfus's projected career path within the Army was in the General Staff, an important but basically bureaucratic role; not a combat role. The argument against his promotion because of missing experience might be claimed less strong for this reason.

- The missing-experience argument might also be less strong because the promotion Dreyfus received was so small; his new job duties would not really require much additional skill or experience.

- Dreyfus consistently refused to accept money as compensation, which had he accepted it would have made matters simpler for the Deputies and the Army. His refusal of money removes some money-related questions (like the amount of back pay due for his deemed service in the "what if" scenario) from needing to be answered.

- Dreyfus was admitted to the Legion of Honour when he rejoined the Army, but this was nearly automatic for officers at his new rank, and it was not seen as a special distinction beyond the rank promotion. Picquart was already a member before the Affair.

- Picquart's promotion was bigger than Dreyfus's, from lieutenant-colonel to brigadier-general back-dated by three years. This two-rank promotion, for a shorter career interruption, was seen as more in line with really achieving the restorative goal. It creates a comparison between the two cases that makes the treatment of Dreyfus look even worse; and it may more strongly raise the missing-experience issues. But much less detail on the specifics of Picquart's case is available to me today.

To analyse the extent of the promotions, it is important to have a clear idea of how ranks worked in the French Army at the time. Here is a summary of the English-language rank titles that are relevant to the Dreyfus and Picquart cases, from highest down to lowest:

- Brigadier-General

- Colonel

- Lieutenant-Colonel

- Major

- Captain

There were often multiple different French titles for a given rank level, depending on which branch of the Army the officer served in, such as artillery or infantry. Ranks as such, the headings on that list, represented big steps in prestige: any major was significantly above any captain. But for officers at the same rank, seniority mattered, and was measured by time since achieving the rank. An officer who had been a captain for several years had more prestige, better pension eligibility, possibly better pay already, and would expect to be considered for promotion to major sooner, than one only recently promoted to the rank of captain.

All those mentioned above are commissioned officer ranks. They entailed tertiary education, and the men in these ranks (and they were all men) were officers and gentlemen, considered to be in a distinct and high social class even in civilian life. Young captains like Dreyfus at the time of his marriage in 1890 were not allowed by official regulation to marry women who had less than a certain minimum amount of family wealth as measured by the value of their dowries. In fact, Dreyfus's wife's family was far richer than the minimum; but this bar was set high enough to be a real obstacle to marriage for some of his peers. The point was to maintain a public perception that military officers were a cut above ordinary people. The democratic ideal of eliminating class from society, given at least lip service in the founding of the Third Republic, was very popular in some quarters, but also very unpopular in others, of French society at the end of the 19th Century. Levelling of society was unpopular within the military.

It does not seem that just promoting Dreyfus from captain to major after twelve years really represented how far he would have advanced in a normal career. At the time of his arrest he had been considered an up-and-coming young officer with good prospects. Someone like that could reasonably have expected promotion to major in less than twelve years, quite possibly to lieutenant-colonel within twelve. The questions of how good his prospects at the start of the Affair really were, and how good a career ought to have been hypothesized in the what-if game, are not easy to answer.

Dreyfus had mostly good reviews from superior officers, and some bad ones, in his file at the time of his arrest. Latter-day writers are quick to dismiss all negative comments from his contemporary evaluators as simple anti-semitism, but that may not be an accurate explanation. His ranking (referring to educational achievement, not authority in the Army) was 9th out of 81 graduating officers when he left the École supériore de guerre, as mentioned below, a pretty good showing; but focusing on that particular ranking smacks of cherry picking, because similar rankings at earlier stages of his education had several times put him below median.

It might be argued that his being part of the General Staff - basically an office paper-shuffling job - weakened the missing experience argument against Dreyfus's promotion. I wrote above about the concerns of a soldier who might not want to be commanded in battle by an inexperienced officer. In fact, General Staff officers would be unlikely to directly command soldiers in battle at all. But using that to excuse a questionable promotion amounts to saying General Staff officers have less important jobs than other officers, and don't need real skills to do their jobs; probably not a true statement, and certainly insulting to them. Furthermore, Dreyfus's training was designed for combat command roles, his rank made him eligible for combat command roles, and he did end up in such a role in the First World War once it began. If majors in general had jobs requiring experience, then Dreyfus as a major needed experience too.

Here is a quote from Alfred Dreyfus himself, in a diary entry at the time of his retirement in 1907. The translation is from Whyte's chronological history of the Dreyfus Affair, and the internal quote at the start (not clearly delineated in Whyte) is from the draft of the Chamber of Deputies bill authorizing the promotion.

The government is powerless to repair the immense harm, both material and moral, which the victim has suffered from such a deplorable miscarriage of justice. It wishes at least to replace Captain Dreyfus in the position he would have reached if he had pursued the normal course of his career.

Yet, on 13 July 1906, more than one hundred artillery officers, less senior than me as captains, were already majors. In appointing me a major, the law recognized that with my ranking when I left the École supériore de guerre, my personal dossier, the same would also have applied to me. Consequently it would have been equitable to give me my legitimate position in seniority among the officers of my weapon-section.

On the date of 13 July 1906, M. de Laguiche, an artillery officer of notably less seniority than me as a captain, was already a lieutenant-colonel. But I had not sought an exceptional promotion.

Among the hundred or more majors of lesser seniority than me as captains, the first promoted to commander [sic] was on 12 October 1901. It would thus simply have been fair to give me, at the time the law was voted, the same seniority as major.

The word "commander" in this translated quote does not make sense. That word in English refers to a naval rank that might be equivalent to lieutenant-colonel in the army; or generally to any officer in command of a given unit, regardless of rank. As far as I can tell there was no specific rank called "commander," or a French term that would be well-translated to English as "commander," in the French Army at the time. I think the only interpretation that really makes sense is that in this sentence Dreyfus wrote commandant, which was one of several French terms for the rank usually translated as "major" but which could also be used untranslated in English; that is, the same rank to which Dreyfus was promoted on reintegration.

I think writing "commander" instead of "commandant" may have been an error, perhaps not in the translation but in the editing of Whyte's book. I have found several other apparent editing errors in that book. So far I have not been able to obtain the original French text for this passage, but I am still trying, and when I have that, I may update this note. It makes an important difference because if somehow "commander" in the translation actually did mean "commander" in English, then the suggestion that Dreyfus should have "the same seniority as major" as someone at a rank equivalent to lieutenant-colonel, would be confusing and would imply some other theory of how to do the calculation.

Assuming the reading "commandant," Dreyfus is saying that he wants to be promoted to the same relative position in seniority order among his peers at the time of his rejoining the Army, that he was in when he left. That is a reasonable, though certainly not the only reasonable, way of interpreting the stated intention of the Chamber of Deputies to put him where he would be "if." He is defining his seniority in terms of who is below him: the comparison group is captains with less seniority than Dreyfus at the time he was kicked out of the Army. None of those men should end up above him in seniority now. As a compromise he limits it to those captains who only made it to the rank of major, excluding the redoubtable de Laguiche and any others who may have been promoted to lieutenant-colonel. Insisting that the Army really should promote nobody from below Dreyfus to be above him during the lost years of his hypothetical reconstructed career, not even de Laguiche, would mean Dreyfus also demanding the rank of lieutenant-colonel (two ranks of promotion instead of one) upon his return.

I have a lot of sympathy with treating the focus in the "what if" scenario as "don't promote more junior officers past him." Having somebody one considers lesser promoted past one, hurts. It has happened to me. There's a university where, if they ever wanted to hire me (won't happen, but), well, they would damn well have to put me higher on the organizational chart than Professor so-and-so who was promoted past me years ago without deserving it. But that approach to justice is very much focused on the individual, on giving someone what he wants and has morally earned, and it may really be more a matter of retribution than restoration. It may not be the right answer to how to deal with the Dreyfus case from the point of view of the institution of the French Army. The idea that it is vexatious to promote someone more junior past Dreyfus, considering him relative to others, does not really address at all the question of his absolute fitness for duty: whether years of rotting in prison, and more years in civilian life without performing Army duties, really gave him the skill to serve in the role of a higher-ranked officer.

A different way to do a similar calculation, still relative to others but much less favourable to Dreyfus, would be to consider other officers who were above him when he left, as the comparison group, and then promote him as far as possible without passing any of them. Very likely, at least one of his peers defined that way was never promoted at all - and then Dreyfus would not be promoted, either. I cannot strongly argue that that calculation makes any less sense than the calculation Dreyfus asks for; it is just the same thing with a different arbitrary choice of the comparison group.

If I were trying to design a general rule for procedural fairness in this kind of case, given we agreed on this kind of relative calculation in the first place, I think the rule that might really be fairest would be to combine them. Pick a representative comparison group including officers who were both above and below Dreyfus when he left, and still in the Army themselves when he returned. Then promote him to the same order statistic of rank and seniority within the comparison group as when he left. That is, he should end up with the same number of men in the comparison group junior and senior to him as before, even though probably not the same individuals because some would have been promoted faster or slower than each other. If anyone passed him, this calculation would force it to be equal numbers passing him in both directions, which seems to keep him at the same relative level if the comparison group is really representative of his peers.

The order-statistic procedure would probably give him a little less seniority than what he asked for, but still significantly more than he was actually given. It still has a theoretical bias in his favour because of not counting officers who might have left the Army. There's an interesting question in how far the "what if this Affair had not happened?" scenario should factor in unlikely possibilities that could occur in 12 years of an officer's career: like his dying unexpectedly, committing some other crime and being punished for that instead of the false espionage charge, doing unusually well and being promoted beyond the rank of major, and so on. The answer to that question would bear on who should be included in the comparison group.

I agree with his position, as far as this point goes and if we agree that promoting Dreyfus at all was the right way to give him justice, that on one calculation basis or another, he should have received more deemed seniority with his promotion than just the day of the Chamber's decision - especially because they gave Picquart extra seniority on what ought to have been the same moral theory. Procedural fairness: the same rules should apply to everybody.

Picquart received a promotion of two full ranks, plus seniority. He had been a lieutenant-colonel when he left the Army in February 1898, and was reinstated as a brigadier-general in July 1906, skipping past the rank of colonel, with his seniority as brigadier-general counted from 10 July 1903. By doing that the Chamber opened the door: they made it clear that they recognized the seniority date as relevant to the restorative goal, and as a thing they could adjust in order to achieve that goal. They also created an inevitable comparison between the two recipients. Multiple commentators said that the decision ended up being fair for Picquart but not fair for Dreyfus.

I have not been able to find a detailed explanation of the basis on which Etienne decided (or claimed to have decided) exactly how much rank and seniority to award Picquart. Although Picquart was kicked out of the Army by forced retirement in February 1898, the Army had been trying to get rid of him with postings increasingly distant from Paris as far back as November 1896; so the interruption of "the normal course of his career" might properly have been judged longer than just the time he spent officially retired, let alone his pre-trial imprisonment connected with the abandoned court-martial. In October 1906, Picquart was appointed Minister of War in the cabinet of Georges Clemenceau, succeeding Etienne.

Dreyfus did seek the additional promotion to lieutenant-colonel, applying to the new Minister of War Picquart for it in November 1906, a few months after his reintegration to the Army. The application was denied.

Burns writes that Dreyfus and Picquart were not personally friendly, despite their linked destinies. The Clemenceau government had benefited from its connection to the Dreyfus Affair, but Dreyfus's conservative political opinions and upper-class family background were not aligned with the new government's left-wing stance. They liked him better as a symbol than as a man. The Dreyfus family and Picquart had fallen out in 1900 over differences in strategy after the second court-martial, linked to personality conflicts between members of the family's legal team; and Picquart retained his general anti-semitism throughout the Affair.

I think Dreyfus may have believed that even though it was a bigger request, it would be more possible for the Army to give him the promotion to lieutenant-colonel in November 1906 than to change the deemed seniority of his promotion to major after the Chamber of Deputies had fixed that. He may also have thought that the Clemenceau cabinet, and Picquart as its minister, would see the what-if calculation differently from the previous cabinet. On a scarcity theory, if higher ranks do in fact require skills developed through training and experience, his spending a few months at the level of major might have allowed him to demonstrate that his skills really were good enough for the further promotion.

But the Dreyfus quote above dates from his retirement in 1907, and it may be his saying in 1907 that he would be satisfied with promotion to major with seniority represented a compromise from an earlier hope for restorative promotion all the way to lieutenant-colonel. It also seems significant that the promotion to lieutenant-colonel he requested through Picquart, if granted, would have been a recognition of him by the Army, and by a Minister of War with real military credentials, therefore more honourable; whereas his promotion to major was something imposed on the Army by the civilian politicians.

Money questions and specific performance

The Dreyfus family was wealthy to begin with, and Alfred had married up: his wife's relatives, the Hadamards, were even wealthier. He had access to some luxuries during his student days that most of his classmates lacked, making him subject to envy and resentment on the part of the other students. Later, his wealth fed into anti-semitic stereotypes and hatred. But it also meant that he did not really need his Army pay. That no doubt factored into his decision to refuse any attempt at compensating him with money for the mistreatment he had suffered. He always maintained that his goal was to restore his and his family's honour, and that it could not be done by writing a cheque.

If money had been more significant, then there would be calculations to make in relation to his hypothetical reconstructed career. For instance, we might go back and calculate the back pay he should have earned for each year of service, with his hypothetical rank at each point. That in turn would make the deemed dates of any intermediate promotions all the more significant; and then to really do it right we should also keep track of interest on the money, accounting for the fact that he was receiving it late. Because he categorically refused to accept money, all these questions are off the table and were never resolved.

In the English legal tradition there is a distinction between the jurisdiction of a court of common law, which will award only money to persons who have been wronged; and a court of equity, which can potentially award (among other possibilities) a remedy of specific performance. That is, the equity court can require somebody to do something, beyond merely paying up, in order to right a wrong. The term "specific performance" is now most often used narrowly to describe enforcement of contracts in particular, but I am using it more generally here to describe remedies for other harms as well as contract breach, which does reflect this term's history. Most courts in most places that inherit from English law today combine the "common law" and "equity" jurisdictions in a single court; there are just a few places which retain separate courts of equity. But even in courts that descend from the English tradition with a partial or complete equity jurisdiction, there is a strong preference for awarding just plain money if at all possible.

The Dreyfus case is a good example for why common law courts prefer to award money damages. There was really no specific performance that could have made him whole. Failing to promote him would have been unfair, and would have failed in the stated goal of putting him back where he ought to be; but promoting him also failed in that goal. They could give him the official job title of a more experienced officer, but they could not cause him to really be the more experienced officer he deserved to be at that point in his career, and without that experience, the title would be worth much less than it should. If only they could have just paid him off and had him go away! Although money also would not recreate his career, it would have fewer externalities, and the question of how much money ought to be paid, despite its obvious complexity would still be much simpler than the question of how to compensate for the aspects of specific performance that were impossible to fulfill.

But France did not (and still does not) follow an English common law tradition. The legal code system used in French courts usually prefers specific performance; and this was not really a court case anyway. The Chamber of Deputies was under no obligation to follow judicial customs in compensating Dreyfus. It is understandable that he would see mere money in any amount as an unacceptable substitute for the career he had lost, or even just those parts of a bright military career he could still have. It is also to be expected that the public would demand to see a greater gesture than money, and that therefore the Chamber in its efforts to placate the public would attempt to grant more than money.

When he retired in 1907, Dreyfus's official rank was reduced to that of captain. This technical demotion appears to have been customary for an officer retiring from the Army, and not seen as any dishonour. He was given a pension according to his accumulated years of service. See Appendix B for a discussion of exactly how many years of service that was. The retirement was not complete or permanent. Dreyfus became part of the "reserve officer corps." When the First World War began in 1914, the Army called up the reserves, bringing him back to the rank of major. He served in the garrison near Paris for most of the war but fought in the Second Battle of the Aisne in 1917. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in September 1918, shortly before the armistice in November of that year.

More about scarcity and abundance

Here is a summary of the attributes of scarcity and abundance, including a few new ones not yet mentioned in the discussion above.

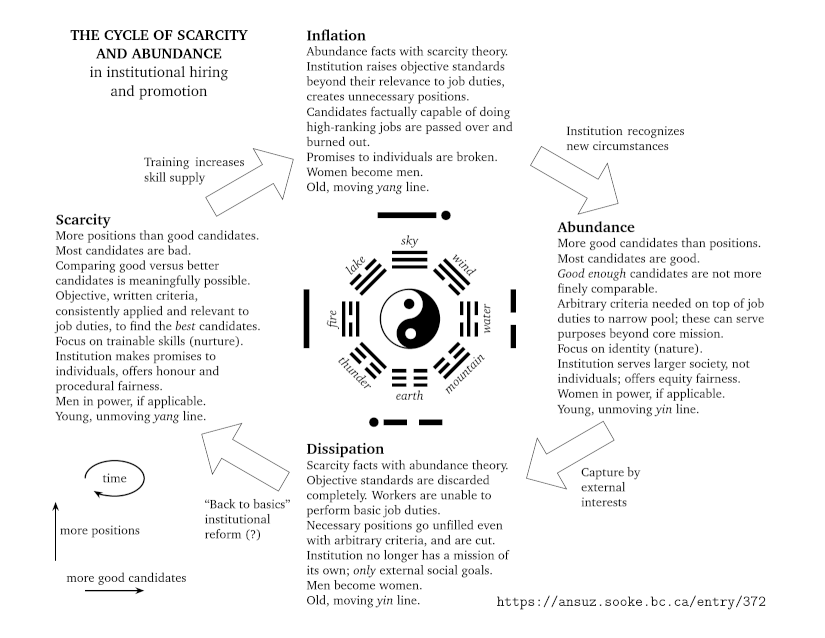

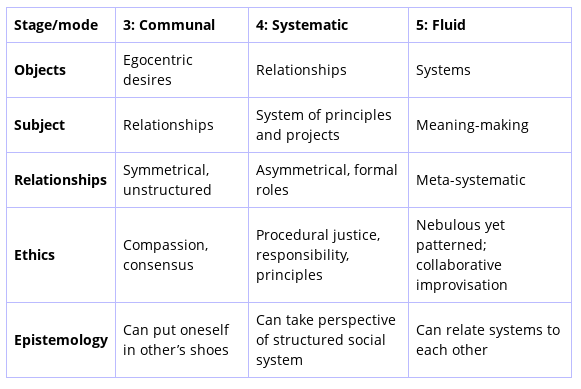

| Scarcity | Abundance |

|---|---|

| More positions than good candidates. | More good candidates than positions. |

| Most candidates are bad. | Most candidates are good. |

| Comparing good versus better candidates is meaningfully possible. | Good enough candidates are not more finely comparable. |

| Objective, written criteria, consistently applied and relevant to job duties, to find the best candidates. | Arbitrary criteria needed on top of job duties to narrow pool; these can serve purposes beyond core mission. |

| Focus on trainable skills (nurture). | Focus on identity (nature). |

| Institution makes promises to individuals. | Institution serves larger society, not individuals. |

| Institution offers honour and procedural fairness, founded on deontological ethics. | Institution offers equity fairness, founded on consequentialist and virtue ethics. |

| Wrongs can be righted by compensating victims with money. | Specific performance remedy is preferred and even necessary. |

| Men in power. I Ching yang line (⚊) . | Women in power. I Ching yin line (⚋) . |

| Institution uses asynchronous, written, and recorded media. Institutional processes happen in public. | Institution uses real-time, non-verbal, and ephemeral media. Institutional processes happen behind closed doors. |

I am hesitant to even mention gender here, because of the danger in the 21st Century climate that as soon as I mention gender at all, readers will perceive this entire article as being about gender and nothing else. This is not an article about gender. Gender was not relevant to the Dreyfus Affair, notwithstanding at least one 21st Century author's attempt to re-cast the entire Affair as about gender starting from the revelation that anti-semitism is actually just a form of misogyny.

This article is not even about the Dreyfus Affair, despite the thousands of words I have written on that example. This article is about institutions.

But given the important role gender did play in another example I want to use - the example of North American universities in the second half of the 20th Century - I would be remiss not to mention gender at all. The values of objectivity in scarcity and subjectivity in abundance are values many writers have often associated with men and women respectively. It is factually true that in North American universities, the time when the institutions operated under scarcity theory was the time when they served a male-majority population and promoted only men, and the time when the institutions operated under abundance theory was the time when they served a female-majority population and often promoted women. I don't think the correlation is only coincidental. For institutions in which gender is relevant, which are not all institutions, male power seems to be part of the pattern of scarcity and female power seems to be part of the pattern of abundance. This correlation feeds into my association of abundance and scarcity with the yin and yang lines of the I Ching, and is further developed in the cycle of facts and theories discussed below.

The media used by an institution also seem related to the institution's theoretical orientation toward scarcity or abundance. Institutions in scarcity with a heavy focus on rules and objectivity gravitate toward using forms of communication with definable meanings, that is, media that use words and are recorded. Because institutional functions occur over time and are not tied to individual human beings - the subjective human element in decision-making is deliberately avoided - there is a preference for asynchronous media. That is, media like written memoranda and (in the present day) email.

Institutions in abundance, conversely, will prefer media that maximize exposure of the subjective human element: those that are nonverbal or allow for nonverbal side channels, such as telephone and video, and certainly real-time media that force human beings to be directly involved with each other. Media that cannot be recorded, or merely are not recorded, are seen as allowing human beings to express themselves without the constraints of future retroactive rule application - which is seen as a positive benefit of these media in abundance and a terrible flaw in scarcity.

I would like to be able to say that the media difference between scarcity and abundance institutional promotion theories is the difference between "hot" and "cool" media described by Marshall McLuhan, but I just cannot make sense of his definitions. McLuhan writes that hot media are immersive media, those which do not require thought from the participants; whereas cool media are more distancing media, with lower sensory fidelity, requiring conscious thought of the participants. By those definitions as I just stated them, the institution in scarcity's preference is for cool media, especially written words: those media that force individuals to use their conscious instead of unconscious mental faculties. The institution in abundance, especially with its emphasis on forcing individuals' emotional states to be legible to each other through real-time interaction and side channels, has a strong preference for hot media like the telephone.

But that seems to be my abuse of McLuhan's terms, because he actually says written words are hot and the telephone is cool, just the opposite of what I write above. A possible explanation is that in his 1964 book he was referring to very specific forms of media exactly as they existed in Toronto in 1964: for instance, his hot radio meant the then-new high-fidelity stereo FM broadcasting, which was mind-blowingly immersive to persons hearing it for the first time, and his cool television meant over-the-air analogue black-and-white, which demanded much from the viewer's imagination. Another clue to "hot" and "cool" is that the difference between two-way and one-way media may be significant. The closely related real time versus asynchronous distinction seems most relevant to abundance and scarcity. That distinction is easier to make precisely, less subject to change as technology changes, and frees me from having to argue with a highly respected dead man.

An institution operating on a scarcity theory will allow, and even prefer, individuals to communicate across time, and to record it. An institution operating on an abundance theory will push them to use simultaneous and ephemeral two-way communication media. As I discuss in Appendix A, the Dreyfus Affair was interesting for its focus on written documents - non-real-time and associated with scarcity in my analysis - but they were handwritten, and much was made of the "graphological" side channels in those documents. How someone wrote a given document was seen as important beyond the words he wrote, and who wrote a document was central to the Affair. Identity emphasis is terribly characteristic of institutions in abundance; so is secret decision-making, another frequent theme in the entire episode. The use of media in the Dreyfus Affair points in both directions.

Now, stepping back and looking at the entire system as I have developed it up to this point, how can the Dreyfus Affair be understood in terms of these two opposing theories? Was the French Army during 1894 to 1906 really in a state of scarcity, or abundance? Do either of them explain well how the institutions behaved? Throughout my comments I have been highlighting the abundance theory in relation to Dreyfus and especially his promotion. Promoting someone as a way to give him back the value of twelve years of experience he never had makes sense in abundance, where the broader social goal is important and the projected negative consequences of such a promotion are not. I think that is the answer: the Chamber of Deputies promoted Dreyfus because they were following a theory of abundance as I have described it, and under that theory, it was the right decision. At the very least, they were playing to an audience that believed abundance theory; the public perceived a high-ranking Army officer as just a more honoured low-ranking officer. If the abundance theory accurately reflected the facts, then they made the right call.

But there are many points in the Affair more consistent with scarcity as I have described it. The Army, as opposed to the Chamber, seems to have operated in many respects more consistently with a theory of scarcity. That may explain why they did not promote Dreyfus much; the Chamber's stated intention was not achieved nor even attempted in good faith. Most of the institutional attributes I link to scarcity theory are attributes of the French Army at the end of the 19th Century. The conflict between scarcity and abundance may parallel the conflict that existed between the Army and the civilian political institutions of the time. Maybe the political institutions were using abundance while the military institution was using scarcity.

It seems clear that Alfred Dreyfus himself was steeped in scarcity theory. He was an officer's officer, with personal values closely parallel to those of the Army institution. He may have been willing sometimes to make appeals to abundance concepts in order to get from the institutions the honour he thought was owed to him for his merit, but he surely was keenly aware of what would be missing from that remedy. Remember that it is institutions in scarcity who make promises to individuals. The very idea of being owed honour for one's personal merit is fundamentally a scarcity concept, expressed in scarcity language.

The conflict between scarcity and abundance theories leads to my next few points. What happens when scarcity and abundance are mixed in the same institution?

Inflation

Suppose there is an institution in the factual situation of abundance. It has plenty of candidates for hiring and promotion, and almost all of them are good. But this institution is operating on a theory of scarcity. It is using processes and policies designed for a factual situation in which most candidates are bad. I call such a combination "inflation." Inflation is misunderstood abundance. It may be linked to what some writers have called "elite overproduction."

The institution following an abundance theory correctly, in a factual situation of abundance, will knowingly turn away many good candidates. It will treat that as a necessity, perhaps unfortunate, but an opportunity to fulfill larger policy goals. The institution in inflation, using a scarcity theory in a factual situation of abundance, will also turn away many good candidates. But the institution in inflation will turn away good candidates mistakenly believing that they really are bad - at least in comparison to others, with an unquestioned assumption that comparing good candidates to each other is possible.

Institutions operating on a theory of scarcity use written objective criteria for promotion and hiring. Confronted with the fact of a huge surplus of candidates meeting the criteria, the scarcity theory says that that means the standards are too low and should be raised. An institution in inflation will raise its standards unreasonably high, while keeping them written and objective.

Often, the inflation effect shows up with respect to educational credentials in particular. It goes all the way up. A job that uses only skills taught in elementary school, will require a high school diploma. A job whose duties are taught in high school will be advertised as requiring a Bachelor's degree. A job that could be done by any PhD holder, will only be open to those with postdoctoral fellowships too, and many single-author papers in top-ranked venues.

Note that although educational credentials are a good example of something objectively measurable that can be subject to inflation, credentials are not the only example. The same thing can happen along other dimensions, even something so prosaic as body weight for a job where that is relevant. Too many good applicants, and the requirements will retreat beyond reasonable limits.

Because scarcity theory deeply embeds the idea that most candidates are bad, the institution that inflates its objective criteria to narrow down a huge pool of candidates will not perceive itself as introducing an arbitrary filter just to narrow down the pool. The institution is more likely to perceive the issue as something wrong with the validity of credentials, an inflation of the candidates' scores rather than an inflation of its own demands. High schools aren't what they used to be. They're graduating too many kids who can't read. We need to require a Bachelor's just to be sure candidates will have everything it says in the high school curriculum. Or even, yeah, well, in that country they hand out PhD parchments like lollipops, so we need to see publications too, and they'd better not be in Hindawi open-access journals.

Another way an institution in inflation may respond to abundance facts is by creating new positions. Because it is following the theory of scarcity, it assumes that most candidates are bad; but hard-to-ignore clues suggesting the factual existence of many good candidates may be interpreted as only meaning that the entire pool of candidates, and the institution's world, are growing. Then the institution tries to grow with the world. Because the real issue is structural - an underestimated proportion of good candidates - the attempt at growth will not be enough. The institution grows with the total pool of candidates, but the also-growing proportion of good candidates means the number of good candidates grows faster than the total pool. Institutions that produce their own candidates (such as universities) also produce more of those as they grow, creating a feedback loop that neutralizes much of the benefit. From an individual candidate's point of view, opportunities for prestige and recognition will seem to be vanishing despite an increasing raw number of positions.

Institutions that believe in scarcity perceive a need to motivate candidates to seek promotion; and the institutions do this partly by making promises. If you reach this objective standard, says the institution, then you are really allowed to expect this promotion. They also promise money and status to the ones who do get promoted. In true scarcity, these promises are easy to make and easy to keep. But in a state of inflation, the promise of promotion for every qualified individual cannot possibly be kept. There are not enough positions for them. And the institution that tries too hard to keep that promise, creating new positions it does not need, will run out of money and status to give the holders of those positions, and will end up breaking the other promise. Okay, you got your high-ranking job title, but your responsibilities and what your salary can really buy are much less than you expected. You are a victim of inflation.

When the factual situation is one of abundance, it is absolutely necessary for the institution to introduce arbitrary criteria, just to narrow down the list of candidates to manageable size. That is an opportunity to use the hiring and promotion criteria for broader policy goals, but only if the institution understands it is in a state of abundance. Inflating objective written criteria far beyond the levels where they are actually relevant, is the inflationary institution's reflexive attempt to thin the herd without apprehending that it is introducing irrelevant arbitrary criteria out of necessity. The equity goals that might be achieved in correctly-recognized abundance, will not be pursued in inflation.

Institutions following scarcity fundamentally believe that relevant objective criteria are appropriate, necessary, and even possible. This belief is embedded so deeply in scarcity theory that it is unconsciously applied everywhere, and never examined directly. Really, in a factual situation of abundance, objective criteria are not very important and may not be possible or desirable. The real differences that make one candidate better than another beyond basic competence are not things the institution can measure; it should not try. Furthermore, in abundance theory the differences that make one candidate better than another beyond basic competence turn out to be inherent qualities that cannot be improved with training. So effort spent on training in particular, trying to change good enough candidates to make them better than good enough, is wasted nearly by definition; that just isn't a correct way to think about the differences among candidates.

Versions of "basic competence" inflated to a level where a majority of good candidates will fail to meet them, become counterproductive. Searching for more and tougher objective criteria to use when there are too many good candidates making it through - misperceived as too many bad candidates making it through - leads institutions to start applying criteria that don't work and even correlate negatively with basic competence, but at least they produce numbers, damn it!; because scarcity theory demands numbers. Consider student bubble-sheet evaluations of teaching performance, which are the most inflationary method of job performance evaluation in human history.

Applying inflated training-based filters costs the candidates, the institution, and society at large far more than other filters that could work just as well. How much does it cost the world to put entire generations through four-year college degrees that they don't need, burning years of lives and massive quantities of money, just so an HR department will have what it can say is an objective basis for throwing out a percentage of resumes for a job that really only requires high school? Rolling a die would work just as well, would be fairer at both the societal and individual levels, and would be a lot cheaper. That should be done instead! - but only if the facts really are facts of abundance.

The institution in inflation ends up discarding candidates who really are at least as good as the ones who made it past the filter, and certainly good enough. It has a terrible human cost for candidates. They put great personal investment of time, money (often borrowed), and foregone opportunities just to meet the published objective criteria for career advancement - and then the promise is broken. When they reach the level of training and objectively-measured skill they were aiming for, it is no longer enough. The new standard is inflated out of reach. Or, maybe the official published standard is still the same, but they just don't get promoted, or don't get interviews, and there is no obvious reason why not.

These people believe in scarcity theory themselves, so they believe it is meaningful to say that some candidates are objectively better than others. If they don't get hired or promoted themselves, it must be because they are among the bad ones after all. And it's too late to do something else with their lives and do really well at it.

The institution in inflation is constantly shedding burned-out candidates who genuinely qualified for promotion but did not meet the unreasonably high arbitrary standard to actually get it, many of those for every single candidate who does get promoted. They go out looking for positions elsewhere, but with unrealistic expectations and many lost years of inapplicable experience; an entire social class of Dreyfuses. It's not clear what can possibly be done with, or for, persons who received expensive and time-consuming training to take up promised jobs that don't exist. Parts of their lives have been wasted.

But the broader society is still likely to call the victims of institutional inflation "privileged" or "elite" and expect gratitude and service from them. Words from Psalm 137:3: "they that wasted us required of us mirth"; the subsequent verses are graphic in describing the psalmist's righteous anger. Persons placed in this situation are likely to have a destabilizing effect on society as they try to take back what they perceive as having been taken from them. That is an externality: a cost of the institution's misguided decisions, stemming from the incorrect application of scarcity theory to abundance facts, that ends up borne by the larger society.

Dissipation

Suppose an institution is in the factual situation of scarcity. It has too few good promotion candidates to fill its high-ranking positions, because most candidates are bad. But this institution is operating on a theory of abundance. Its processes and policies assume a situation in which almost all candidates are good. I call this combination "dissipation." It is misunderstood scarcity, and the natural opposite of inflation.

Because the institution in dissipation is following an abundance theory, it perceives hiring and promotion as opportunities to fulfill policy goals that extend beyond itself into the general society. Moreover, because abundance theory states that almost all candidates are good, and residual differences between good enough candidates are institutionally unknowable, the institution in dissipation concludes that it doesn't really matter who gets promoted. Whereas the institution in true abundance knowingly turns away some good candidates along with the bad ones out of mere necessity, the institution in dissipation both turns away and promotes both good and bad candidates indiscriminately, mistakenly believing that to do so makes no real difference either way. Note that the very word "discriminate" is a bad word in abundance theory; the institution in dissipation concludes that that word's opposite must be good.

My description of abundance theory was peppered with the phrase "basic competence." Abundance theory in its best applied form limits the use of objective criteria to verifying basic competence - which is assumed to be easy to recognize, and is not highly salient because almost all candidates do have basic competence when the factual situation is one of abundance. But if the factual situation is actually one of scarcity, then basic competence is not anywhere near guaranteed in the candidate pool. The objective standards that would test for it become much more salient in scarcity than abundance theory expects they should be. The number of candidates failing the "basic competence" standard is much too high to be reconciled with abundance theory's core assumption that most candidates are good. And just as inflation responds by changing the objective standards, dissipation also changes the objective standards, lowering them or more likely eliminating them entirely.