Somebody but not anybody

Tue 20 Sep 2022 by mskala Tags used: philosophy, religion, cargoWe have a patient suffering kidney failure; he's in a lot of pain and the disease will soon kill him. He could be saved - if someone would donate a kidney to be transplanted into this patient's body. So, as a matter of ethics, somebody ought to do that, right?

But who, exactly?

Donating a kidney is a big deal for a living person. It will endanger the donor's health and likely shorten their lifespan. Most non-monstrous theories of medical ethics would teach that we can't take somebody's kidney without their consent, and they have an absolute right to say "no." And there are perfectly understandable reasons someone actually would say "no."

Most of us also accept the even stronger position that it is ethically forbidden to so much as take organs for this purpose from a dead body, if the deceased while living refused to give permission for that. The argument that a dead person no longer has anything to lose from the donation doesn't carry enough weight to override the sacral status of consent, and more complicated and situation-specific issues (like the horror of creating any incentive for deliberately killing people to harvest their organs) come into play.

What we have here is a situation where somebody in general - hypothetically - ought to do something that we are not allowed to expect from anybody in particular in real life.

I'm interested in deontology - obligations as the fundamental basis for ethics - and especially in situations like this where it seems like there's a general obligation on a hypothetical "somebody" that it is taboo to claim from any specific real person. Such a situation is logically incoherent, but it's not going to stop being real just because it makes no sense, and how people and systems try to deal with the contradiction says a lot about both.

*

The kidney-transplant example has a lot of specific details that could distract from the general principle I want to illustrate. For example, there are always other treatment options, more or less likely to be useful, besides specifically a transplant from another human being; and statements like "this patient will die" and "that patient will not" are always probabilistic, without guarantees in either direction. As you know, I hate giving examples for general principles I want to talk about, because of the inevitable focus of responses on non-general details of the examples.

A more vague and lower-stakes situation with the same shape comes up in the context of taxation, and makes possible a connection to left/right politics. Of course, I mean those terms in their traditional meaning and not the wacky clown world "left" and "right" tribes currently visible in North America.

Some people, for various reasons we don't need to go into here, need resources they can't provide for themselves but that can be bought with money. "Somebody" ought to help them. But who?

What might be called a right-wing view favours voluntary charity: the idea that members of society will individually and voluntarily donate to support those who need it. But it's emphasized that this must be voluntary. It fails with no answer to the problem if nobody actually does make the choice to donate; and it has other problems regarding the gap between what voluntary donors think needs to be done, and what actually does need to be done.

What might be called a left-wing view favours the idea that an obligation on society at large actually does bind individuals in the society: so that taxes or other enforced taking of money and other resources to give to those who need them, is both allowable and admirable. Then the recipients may get what they need, but the compelled donors can reasonably protest, "Why me? There's no reason that I should be the 'somebody' who provides for this need."

As I've written before, the left hates individual merit - or individual responsibility - and the right hates social contracts. Both are wrong; but that doesn't make it much easier to find the correct answer, as a compromise between them or in any other way.

Money makes it much easier to resolve these things because, for needs that can be satisfied with money, it makes possible a more equitably distributed kind of giving and taking, compromising between the left and right extremes. We don't need to single one person out to provide a home for a homeless person; we can require everyone to pay a small amount of money, with the obligations calculated in a precise way we consider fair, and then go buy what's needed on the market. Maybe nobody is completely happy about paying their share of taxes, and it's possible to argue endlessly on the details of how taxes are collected and spent - as people do in real-life politics - but it's also easy to say that it's better than letting people starve or freeze, and better than singling out individuals to make unequal compelled donations.

But it only works for whatever we agree can be bought with money. It also only works to the extent we're willing to accept that some kind of compromise, not an extreme hard line one way or other other, can be possible and would be desirable.

*

I've written under the heading of scarcity and abundance about the matter of institutions making promises to individuals about their lives and career paths, especially in the state of "inflation" and the days of scarcity leading up to it. "Invest your life into this training," the institution says, "and you will be allowed to expect this career, with its attendant money and status."

Maybe in the case of an institution like the Army, which can both provide the training and a place for the trainee afterward, that is a straightforward obligation that we can think of like a contract. But very often, a part of the inflationary breakdown I described in the earlier piece is exactly the kind of "somebody but not anybody" obligation I have in mind now.

A university offers training at great cost to the student, supported by the implicit or often explicit promise that somebody will give them a good job afterward. But who? Not the university itself; it is simply not in that business. Not any specific employer; most places have a more or less free market in employment, and no employer is obligated to hire anyone in particular. Not anybody; just somebody.

Free markets that separate training and employment make it easier not to see the somebody/not anybody issue because it's clear that the training providers are not responsible for the employers' actions. But such markets also make the problem bigger and more likely to occur, even as we find more excuses not to apply responsibility anywhere in particular.

The tension between a general promise and no specific party obligated to carry it out, makes the situation all the worse when the markets shift from a scarcity to an abundance of qualified persons. In scarcity, there really would be some employer eager to hire each graduate. Once abundance of employees becomes factually true, with more persons chasing fewer jobs, it is no longer practically possible to count on "somebody" to hire each graduate; but the promise will keep being made for a long time after the facts have changed.

"Somebody but not anybody" applies at other levels of the academic system too, of course. If a researcher writes a good paper, some journal or conference will publish it, right? But which one? The researcher is absolutely not allowed to demand it of any specific venue in particular; each one can, and may well, reject the work. The researcher is expected to just keep submitting to more journals as long as it takes, without limit despite the finite number of possible destinations - while, in the state of inflation, acceptance or rejection of papers will be one of the inflated objective criteria over which the researcher suffers career penalties.

*

There might possibly be some interest in trying to map the problem with symbolic logic. As a first attempt we might take a variable x, let Y be the statement that x has a given obligation, and write:

- ∀x ¬Y "For all specific x, it is not the case that x is obligated."

- ∃x Y "Somebody is obligated."

These two statements are exactly opposite, through the replaement of "∀x" with "¬∃x¬" followed by double negation. Each is true if and only if the other is not true. They cannot both be true; together they are nothing but a contradiction. But maybe that's just because I used the wrong kind of symbolic logic. The second point above might be more correctly read as "there exists a specific person who is obligated" and it's unsurprising that that would be contradictory when we're also trying to capture the statement of just the opposite of that.

A more advanced deontic modal logic includes an operator O for things that are obligatory. Note the similarity of the word to "deontology," which comes from the fact that this is a logic specifically designed to capture obligations. Reasoning about obligations may require including the special nature of obligations in our rules of logic, instead of just sweeping them into (meta)variables. Consider:

- ∀x ¬OY "For all specific x, it is not obligatory that x should do Y."

- O∃x Y "It is obligatory that there is some x who does Y."

From a pure symbolic point of view, that resolves the contradiction, because there is no reason the O needs to interact in any particular way with the quantifiers ∀ and ∃ (nor even with the negation ¬). The manipulation of the first statement that caused problems in non-modal logic, no longer works here on the symbolic level to produce exactly the opposite of the second statement. But it may be all we're doing here is trying to wave away the original question of whom an obligation falls on, by talking about acts being just kind of "obligatory" in general without saying on whom. The O outside the quantifier seems to refer to a very different specific obligor, if any, than O inside the quantifier.

I don't know a whole lot about modal logic in general, let alone deontic modal logic in particular, but it seems worth thinking about at least a little more.

*

One of my own very few hard lines, when it comes to social media, is any kind of victim-blaming that targets lonely persons. Pull that shit and you stand a good chance of being unfollowed, blocked, or similar.

I try to make allowances for the fact nearly all of what people post on social media is just signalling the kind of person they want others to see them as, and not reflective of deeply held and deeply considered personal beliefs. But if you even casually want to be seen as the kind of person who thinks it's any lonely person's fault they don't have a partner, then that's a red flag for me, to say the least.

There are several former friends I no longer have contact with because they pushed that idea too hard, too many times; and I had a near miss with one recently on Twitter.

It's another somebody-but-not-anybody matter. It's not hard to construct a fallacious argument that anyone who wants a partner has "several billion eligible members of the opposite sex" [I would say: preferred sex, according to orientation] to choose from, as was literally said by another Twitter account whom I did block recently, and so if somebody is still lonely in such a world it must necessarily be the lonely person's choice and fault, obviating any sympathy or obligation on the part of a passing starfish. If the lonely human made a level of effort, and accepted a level of compromise to their goal, that we should reasonably demand, then "somebody" would accept their offer. Who? Well, it's that hypothetical "somebody" again. Not anybody in particular who actually exists. Just "somebody."

"Somebody" is an amazing hypothetical person whose sacrifices wash away all the sins of specific real people - and that's a clue.

I'm well aware - it is the point of this article - that assigning blame or responsibility is difficult when there's a gap between what we expect of a hypothetical "somebody" and what we're allowed to expect of specific real individuals. But concluding from this theoretical difficulty that the moral or practical responsibility devolves onto the person who is being directly harmed by the situation, is the worst way of purporting to resolve the theoretical difficulty. That's like saying it's the kidney patient's sole responsibility to find a donor, that they surely could if virtuous enough, and so if they do die, it's their own fault.

If we're treating consent as a requirement beyond question, and if we have a "theory of mind" (meaning, acceptance of the reality that the universe contains more than one person), then pairing up is pretty much exactly the one thing most absolutely impossible to do alone!

I don't know what kind of mental distortion it takes to see victim-blaming as a reasonable position to take in that space, let alone the moral distortion involved in someone whom I know cares deeply about what's right (and has religious faith at a level I myself don't) seeing victim-blaming for loneliness as an ethically acceptable position, worthy of prosyletism.

*

Of course, one way to wave away such problems to is simply deny the theory of mind. I've visited religious contexts in which the claim was taken seriously that the number of meaningfully existing persons in the universe is not greater than (let's dig out the capital letters here) One.

If All are One, then any gap between an obligation on All and an obligation on One, is an illusion; there is no difference between those two things. Being able to look at the obligation and whatever created it while - temporarily, as an exercise - factoring out the annoyingly contradictory part of the ontology, may well be an exercise that allows us to find some useful new things to say and a new understanding of what's going on that can also be applicable in contradictory baseline reality.

To say that All are One is a mystical truth. It's an as if statement that may be useful to consider as a way of tricking our brains into finding new ideas, but which cannot be relied upon as a factual description of baseline reality.

In fact, persons do exist. More than one of them! And much like other mystical truths, the denial of theory of mind is only useful when we know, and are able to contrast this against, the baseline reality. I've met enough people who managed through meditation, drugs, and other things to get their heads so far up their asses that they really couldn't see any other world than the world of All being One on the practical level. It didn't help them actually solve any problems.

*

There is a concept I have encountered in Jewish writings - and it may have a specific Hebrew name, I don't know - that when we begin to do something that is obligatory (a mitzvah), and we are unable to complete it, then God completes it for us in Heaven, even if only in a way that we cannot perceive. This principle has some practical application for instance in certain rituals performed for the benefit of dead persons, who may seem on the gross physical level to be beyond any human assistence. It's a grand idea.

Although I'm not Jewish myself, am unlikely to convert, and I only encountered that concept in codified written form relatively recently, and of course I may well be misunderstanding it, it resonated strongly for me and I feel that believing in it on some level may explain some of my own behaviour, especially at earlier times in my life. This idea amounts to saying that God is the "somebody" who holds the obligation when it is clear that "somebody" has an obligation but we cannot point to any human who is obligated. The buck stops in Heaven, so to speak. From a religious engineering perspective the "even if only in a way that we cannot perceive" clause is a clever way to preserve faith in this principle when facts in baseline reality do not seem to support it - but of course that clause also limits its practical application.

Other religious systems also put one or more gods or divine figures in the role of taking responsibility when no specific individual human being can be held responsible. I alluded to Jesus earlier as someone often described as having something like this function. Sometimes I think that this may be the very purpose of having gods. The gods are the bearers of last resort for moral responsibility, much like a central bank is a lender of last resort, and in monarchies the sovereign is the human leadership authority of last resort. All of these last resorts have important purposes and to eliminate any of them may be a bad idea. Who is the "somebody" responsible for an obligation when there is not anybody human who owns it? Maybe the answer is God, or a god, or some other figure defined by the religious context.

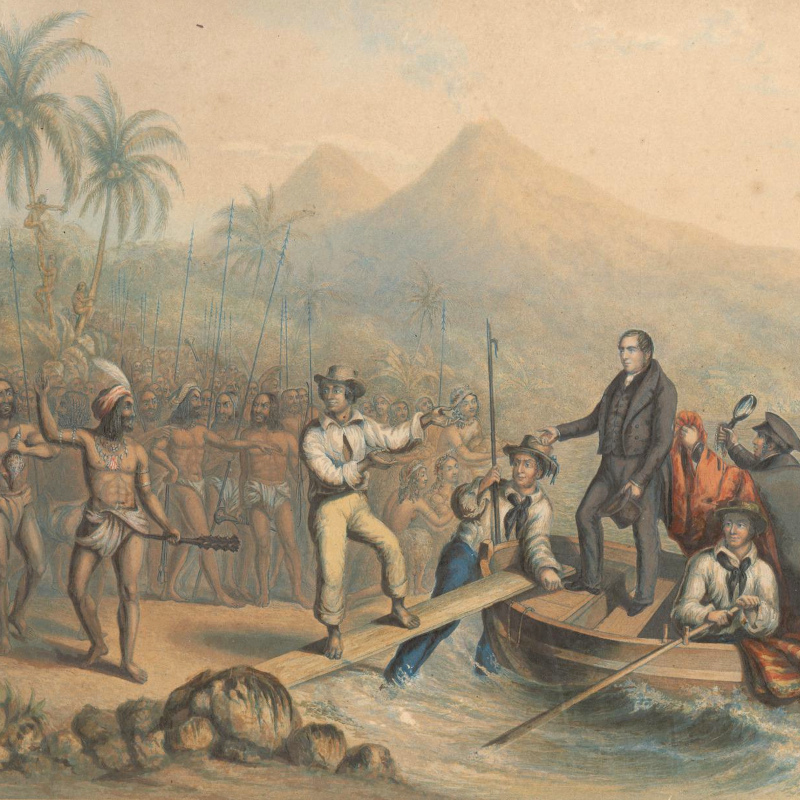

Demanding practical application of such a principle, that one or more gods or religious figures will visibly do that which is missing from human action, veers in the direction of Cargo. There is this idea that feels similar to the Jewish one, but is much harder to justify, that if there is something one human being hopes to achieve but cannot do alone, or even that a group of human beings collectively hope to achieve but cannot do under their united power, then at least they can create the conditions for it, and then if the conditions are created right they may have a real expectation of the supernatural or divine filling in the blanks. Maybe John Frum really will land his airplane on your island, if you build the runway he needs, and really build it right.

Cargo thinking in modernized form, with most of the religious bits filed off, appears in Field of Dreams (1989): "If you build it, he will come." It's a lot of the basis for The Secret (2006) with its "law of attraction," which of course is an approximation or rehash of what New Thought, Christian Science, and a lot of other systems had been saying for decades already. It's the basis of gotta be in it to win it thinking.

The core belief of Cargo seems to be a jump from necessary conditions to sufficient conditions, echoing some of the symbolic logic stuff from before. If you do what is necessary for the result you hope for, then somebody in general - but maybe not anybody in particular, and at least not anybody human - will do the rest, so that what was necessary also becomes sufficient.

The injurious cutting edge of Cargo belief is that if you purport to have done what was necessary to create the conditions for something you cannot complete alone, and it turns out not to be sufficient because you really can't complete it alone, then that's your fault because you didn't really create the conditions after all. That which was necessary from you ought to have been sufficient, the part that comes from outside being an automatic expectation. Such logic is what leads to victim-blaming, by people who would certainly never admit to being aptly labelled "cargo cultists."

Cargo doesn't seem to work very well in practice! But it's a seductive concept, isn't it? Not least because there doesn't seem to really be anything else human beings can do, by definition, beyond, well, whatever human beings can do. If what is possible for us to do ourselves is not enough, then that seems to be the point at which our gods just have to take over - and the point at which any gods who exist and are worthy of worship, really will take over. Who else could we ever call our gods, and what else could we ever call magical?

Although the book's main themes ended up being other ones, I actually started writing Shining Path with the idea that it would be a book about Cargo, in which characters would create the conditions for changes and then expect the changes to actually occur, with or without success. The working title of that book was Kaago, a Japanized version of the English word. Most of the detailed exploration of creating the conditions ended up fading into the background, and if anything the scarcity/abundance theory with its concept of broken promises ended up being a bigger part of what I wrote the book about, even though I hadn't consciously formulated that yet. But there are still a few mentions of Cargo concepts in the text, and even an appearance by John Frum.

Detail of aquatint print by George Baxter, The Reception of the Rev. J. Williams at Tanna in the South Seas, the Day before He Was Massacred:

1 comment

Also ripple seems super important as a conceptual middleground here, too, though there's still a god of the gaps to be found. Giving the "Somebody" account some ripple credit is tatamount to joining a social contract, out of charity. Hell, a generalized ripple ledger could even have such contracts.

jeff cliff - 2022-11-29 18:58